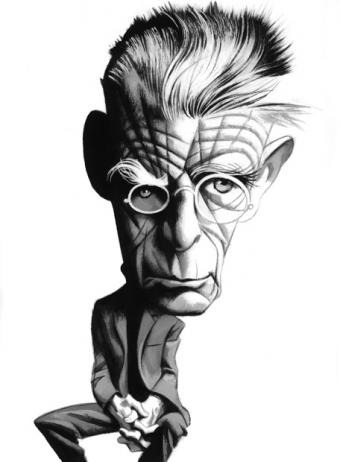

Seamus Heaney

1939–2013

Seamus Heaney is widely recognized as one of the major poets of the 20th century. A native of Northern Ireland, Heaney was raised in County Derry, and later lived for many years in Dublin. He was the author of over 20 volumes of poetry and criticism, and edited several widely used anthologies. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1995 "for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past." Heaney taught at Harvard University (1985-2006) and served as the Oxford Professor of Poetry (1989-1994). He died in 2013.

Heaney has attracted a readership on several continents and has won prestigious literary awards and honors, including the Nobel Prize. As Blake Morrison noted in his work Seamus Heaney, the author is "that rare thing, a poet rated highly by critics and academics yet popular with 'the common reader.'" Part of Heaney's popularity stems from his subject matter—modern Northern Ireland, its farms and cities beset with civil strife, its natural culture and language overrun by English rule. The New York Review of Books essayist Richard Murphy described Heaney as "the poet who has shown the finest art in presenting a coherent vision of Ireland, past and present." Heaney's poetry is known for its aural beauty and finely-wrought textures. Often described as a regional poet, he is also a traditionalist who deliberately gestures back towards the “pre-modern” worlds of William Wordsworth and John Clare.

Heaney was born and raised in Castledawson, County Derry, Northern Ireland. The impact of his surroundings and the details of his upbringing on his work are immense. As a Catholic in Protestant Northern Ireland, Heaney once described himself in theNew York Times Book Review as someone who "emerged from a hidden, a buried life and entered the realm of education." Eventually studying English at Queen’s University, Heaney was especially moved by artists who created poetry out of their local and native backgrounds—authors such as Ted Hughes, Patrick Kavanagh, and Robert Frost. Recalling his time in Belfast, Heaney once noted: "I learned that my local County Derry [childhood] experience, which I had considered archaic and irrelevant to 'the modern world' was to be trusted. They taught me that trust and helped me to articulate it." Heaney’s work has always been most concerned with the past, even his earliest poems of the 1960s. According to Morrison, a "general spirit of reverence toward the past helped Heaney resolve some of his awkwardness about being a writer: he could serve his own community by preserving in literature its customs and crafts, yet simultaneously gain access to a larger community of letters." Indeed, Heaney's earliest poetry collections— Death of a Naturalist (1966) and Door into the Dark(1969)—evoke "a hard, mainly rural life with rare exactness," according to critic and Parnassus contributor Michael Wood. Using descriptions of rural laborers and their tasks and contemplations of natural phenomena—filtered through childhood and adulthood—Heaney "makes you see, hear, smell, taste this life, which in his words is not provincial, but parochial; provincialism hints at the minor or the mediocre, but all parishes, rural or urban, are equal as communities of the human spirit," notedNewsweek correspondent Jack Kroll.

As a poet from Northern Ireland, Heaney used his work to reflect upon the "Troubles," the often-violent political struggles that plagued the country during Heaney’s young adulthood. The poet sought to weave the ongoing Irish troubles into a broader historical frame embracing the general human situation in the books Wintering Out(1973) and North (1975). While some reviewers criticized Heaney for being an apologist and mythologizer, Morrison suggested that Heaney would never reduce political situations to false simple clarity, and never thought his role should be as a political spokesman. The author "has written poems directly about the Troubles as well as elegies for friends and acquaintances who have died in them; he has tried to discover a historical framework in which to interpret the current unrest; and he has taken on the mantle of public spokesman, someone looked to for comment and guidance," noted Morrison. "Yet he has also shown signs of deeply resenting this role, defending the right of poets to be private and apolitical, and questioning the extent to which poetry, however 'committed,' can influence the course of history." In the New Boston Review, Shaun O'Connell contended that even Heaney's most overtly political poems contain depths that subtly alter their meanings. "Those who see Seamus Heaney as a symbol of hope in a troubled land are not, of course, wrong to do so," O'Connell stated, "though they may be missing much of the undercutting complexities of his poetry, the backwash of ironies which make him as bleak as he is bright." As poet and critic Stephen Burt wrote, Heaney was “resistant to dogma yet drawn to the numinous.” Helen Vendler described him as “a poet of the in-between.”

Heaney’s first foray into the world of translation began with the Irish lyric poem Buile Suibhne. The work concerns an ancient king who, cursed by the church, is transformed into a mad bird-man and forced to wander in the harsh and inhospitable countryside. Heaney's translation of the epic was published as Sweeney Astray: A Version from the Irish (1984). New York Times Book Review contributor Brendan Kennelly deemed the poem "a balanced statement about a tragically unbalanced mind. One feels that this balance, urbanely sustained, is the product of a long, imaginative bond between Mr. Heaney and Sweeney." This bond is extended into Heaney's 1984 volume Station Island, where a series of poems titled "Sweeney Redivivus" take up Sweeney's voice once more. The poems reflect one of the book’s larger themes, the connections between personal choices, dramas and losses and larger, more universal forces such as history and language. In The Haw Lantern (1987)Heaney extends many of these preoccupations. W.S. DiPiero described Heaney's focus: "Whatever the occasion—childhood, farm life, politics and culture in Northern Ireland, other poets past and present—Heaney strikes time and again at the taproot of language, examining its genetic structures, trying to discover how it has served, in all its changes, as a culture bearer, a world to contain imaginations, at once a rhetorical weapon and nutriment of spirit. He writes of these matters with rare discrimination and resourcefulness, and a winning impatience with received wisdom."

With the publication of Selected Poems, 1966-1987 (1990) Heaney marked the beginning of a new direction in his career. Poetry contributor William Logan commented of this new direction, "The younger Heaney wrote like a man possessed by demons, even when those demons were very literary demons; the older Heaney seems to wonder, bemusedly, what sort of demon he has become himself." In Seeing Things(1991) Heaney demonstrates even more clearly this shift in perspective. Jefferson Hunter, reviewing the book for the Virginia Quarterly Review, maintained that collection takes a more spiritual, less concrete approach. "Words like 'spirit' and 'pure'… have never figured largely in Heaney's poetry," Hunter explained. However, inSeeing Things Heaney uses such words to "create a new distanced perspective and indeed a new mood" in which "'things beyond measure' or 'things in the offing' or 'the longed-for' can sometimes be sensed, if never directly seen." The Spirit Level (1996) continues to explore humanism, politics and nature.

Always respectfully received, Heaney’s later work, including his second collected poems, Opened Ground: Selected Poems, 1966-1996 (1998), has been lavishly praised. Reviewing Opened Ground for the New York Times Book Review, Edward Mendelson commented that the volume “eloquently confirms [Heaney’s] status as the most skillful and profound poet writing in English today." With Electric Light (2001), Heaney broadened his range of allusion and reference to Homer and Virgil, while continuing to make significant use of memory, elegy and the pastoral tradition. According to John Taylor in Poetry, Heaney "notably attempts, as an aging man, to re-experience childhood and early-adulthood perceptions in all their sensate fullness." Paul Mariani in America found Electric Light "a Janus-faced book, elegiac" and "heartbreaking even." Mariani noted in particular Heaney's frequent elegies to other poets and artists, and called Heaney "one of the handful writing today who has mastered that form as well."

Heaney’s next volume District and Circle (2006) won the T.S. Eliot Prize, the most prestigious poetry award in the UK. Commenting on the volume for the New York Times, critic Brad Leithauser found it remarkably consistent with the rest of Heaney’s oeuvre. But while Heaney’s career may demonstrate an “of-a-pieceness” not common in poetry, Leithauser found that Heaney’s voice still “carries the authenticity and believability of the plainspoken—even though (herein his magic) his words are anything but plainspoken. His stanzas are dense echo chambers of contending nuances and ricocheting sounds. And his is the gift of saying something extraordinary while, line by line, conveying a sense that this is something an ordinary person might actually say.”

Heaney’s prose constitutes an important part of his work. Heaney often used prose to address concerns taken up obliquely in his poetry. In The Redress of Poetry (1995),according to James Longenbach in the Nation, "Heaney wants to think of poetry not only as something that intervenes in the world, redressing or correcting imbalances, but also as something that must be redressed—re-established, celebrated as itself." The book contains a selection of lectures the poet delivered at Oxford University as Professor of Poetry. Heaney's Finders Keepers: Selected Prose, 1971-2001 (2002) earned the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism, the largest annual prize for literary criticism in the English language. John Carey in the London Sunday Timesproposed that Heaney's "is not just another book of literary criticism…It is a record of Seamus Heaney's thirty-year struggle with the demon of doubt. The questions that afflict him are basic. What is the good of poetry? How can it contribute to society? Is it worth the dedication it demands?" Heaney himself described his essays as "testimonies to the fact that poets themselves are finders and keepers, that their vocation is to look after art and life by being discoverers and custodians of the unlooked for."

As a translator, Heaney’s most famous work is the translation of the epic Anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf (2000). Considered groundbreaking because of the freedom he took in using modern language, the book is largely credited with revitalizing what had become something of a tired chestnut in the literary world. Malcolm Jones in Newsweekstated: "Heaney's own poetic vernacular—muscular language so rich with the tones and smell of earth that you almost expect to find a few crumbs of dirt clinging to his lines—is the perfect match for the Beowulf poet's Anglo-Saxon…As retooled by Heaney, Beowulf should easily be good for another millennium." Though he has also translated Sophocles, Heaney remains most adept with medieval works. He translated Robert Henryson’s Middle Scots classic and follow-up to Chaucer, The Testament of Cresseid and Seven Fables in 2009.

In 2009, Seamus Heaney turned 70. A true event in the poetry world, Ireland marked the occasion with a 12-hour broadcast of archived Heaney recordings. It was also announced that two-thirds of the poetry collections sold in the UK the previous year had been Heaney titles. Such popularity was almost unheard of in the world of contemporary poetry, and yet Heaney’s voice is unabashedly grounded in tradition. Heaney’s belief in the power of art and poetry, regardless of technological change or economic collapse, offers hope in the face of an increasingly uncertain future. Asked about the value of poetry in times of crisis, Heaney answered it is precisely at such moments that people realize they need more to live than economics: “If poetry and the arts do anything,” he said, “they can fortify your inner life, your inwardness."

BIBLIOGRAPHY

POETRY

Death of a Naturalist, Oxford University Press (New York, NY), 1966.

Door into the Dark, Oxford University Press (New York, NY), 1969.

Wintering Out, Faber (London), 1972, Oxford University Press (New York, NY), 1973.

North, Faber, 1975, Oxford University Press (New York, NY), 1976.

Field Work, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1979.

Poems: 1965-1975, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1980.

(Adapter) Sweeney Astray: A Version from the Irish, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1984, revised edition, with photographs by Rachel Giese, published as Sweeney's Flight, 1992.

Station Island, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1984.

The Haw Lantern, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1987.

New and Selected Poems, 1969-1987, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1990, revised edition published asSelected Poems, 1966-1987, 1991.

Seeing Things: Poems, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1991.

The Midnight Verdict, Gallery Books (Old Castle, County Meath, Ireland), 1993.

The Spirit Level, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1996.

Opened Ground: Selected Poems, 1966-1996, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1998.

Electric Light, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 2001.

District and Circle, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 2006.

Human Chain, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 2010.Contributor to 101 Poems Against War, edited by Matthew Hollis and Paul Keegan, Faber and Faber (London, England), 2003.

POETRY CHAPBOOKS

Eleven Poems, Festival Publications (Belfast, Northern Ireland), 1965.

(With David Hammond and Michael Longley) Room to Rhyme, Arts Council of Northern Ireland, 1968.

A Lough Neagh Sequence, edited by Harry Chambers and Eric J. Morten, Phoenix Pamphlets Poets Press (Manchester, England), 1969.

Boy Driving His Father to Confession, Sceptre Press (Surrey, England), 1970.

Night Drive: Poems, Richard Gilbertson (Devon, England), 1970.

Land, Poem-of-the-Month Club, 1971.

Servant Boy, Red Hanrahan Press (Detroit, MI), 1971.

Stations, Ulsterman Publications (Belfast, Northern Ireland), 1975.

Bog Poems, Rainbow Press (London, England), 1975.

(With Derek Mahon) In Their Element, Arts Council of Northern Ireland, 1977.

After Summer, Deerfield Press, 1978.

Hedge School: Sonnets from Glanmore, Charles Seluzicki (Portland,OR), 1979.

Sweeney Praises the Trees, [New York, NY], 1981.

PROSE

The Fire i' the Flint: Reflections on the Poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Oxford University Press (New York, NY), 1975.

Robert Lowell: A Memorial Address and Elegy, Faber (London, England), 1978.

Preoccupations: Selected Prose, 1968-1978, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1980.

The Government of the Tongue: Selected Prose, 1978-1987, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1988.

The Place of Writing, Scholars Press, 1989.

The Redress of Poetry, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1995.

Crediting Poetry: The Nobel Lecture, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1996.

Finders Keepers: Selected Prose, 1971-2001, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 2002.

(With Dennis O'Driscoll) Stepping Stones: Interviews with Seamus Heaney, Farrar Straus (New York, NY), 2008. EDITOR

(With Alan Brownjohn) New Poems: 1970-1971, Hutchinson (London, England), 1971.

Soundings: An Annual Anthology of New Irish Poetry, Blackstaff Press (Belfast, Northern Ireland), 1972.

Soundings II, Blackstaff Press (Belfast, Northern Ireland), 1974.

(With Ted Hughes) The Rattle Bag: An Anthology of Poetry (juvenile), Faber (London, England), 1982.

The Essential Wordsworth, Ecco Press (New York, NY), 1988.

(With Rebecca James, Miles Graham, Raphael Lyne) The May Anthology of Oxford and Cambridge Poetry(Varsity/Cherwell, Oxford, England), 1993.

(With Ted Hughes) The School Bag, Faber (London, England), 1997.

Yeats, ( "Poet to Poet series"), Faber (London, England), 2000.

OTHER

(With John Montague) The Northern Muse (sound recording), Claddagh Records, 1969.

The Cure at Troy: A Version of Sophocles'"Philoctetes" (drama; produced by Yale Repertory Theater, 1997, produced in Oxford, England, 1999), Farrar, Straus, 1991.

(Translator, with Stanislaw Baranczak) Laments, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1995.

(With Joseph Brodsky and Derek Walcott) Homage to Frost, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 1996.

(Translator) Beowulf: A New Verse Translation, Farrar, Straus, 2000.

(Translator) Leos Janacek, Diary of One Who Vanished: A Song Cycle, Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 2000.

(Author of introduction) Darcy O'Brien, A Way of Life, Like Any Other, New York Review Books, 2001.

(Translator) Sorley McLean, Hallaig, 2002.

(Translator) The Midnight Verdict (collection), Dufour, 2002.

(Author of introduction) David Thomson, The People of the Sea: A Journey in Search of the Seal Legend,Counterpoint, 2002.

(With Liam O'Flynn) The Poet and the Piper (audio), Claddagh Records, 2003.

(Author of introduction) Thomas Flanagan, There You Are: Writing on Irish and American Literature and History, edited by Christopher Cahill, New York Review Books, 2003.

(Translator) The Burial at Thebes: A Version of Sophocles'"Antigone," Farrar, Straus (New York, NY), 2004.

(Translator) The Testament of Cresseid, Enitharmon Press, 2004.

(Translator) Columcille the Scribe, The Royal Irish Academy, 2004.

(Translator) The Testament of Cresseid and Seven Fables, Faber and Faber, 2009.Contributor to books, including The Writers: A Sense of Ireland, O'Brien Press (Dublin, Ireland), 1979; Canopy: A Work for Voice and Light in Harvard Yard, Harvard University Art Museums, 1997; Healing Power: The Epic Poise—A Celebration of Ted Hughes, edited by Nick Gammage, Faber, 1999; For the Love of Ireland: A Literary Companion for Readers and Travelers, Ballantine, 2001; 101 Poems against War, edited by Matthew Hollis and Paul Keegan, Faber, 2003; and Don't Ask Me What I Mean: Poets in Their Own Words, Picador, 2003. Contributor of poetry and essays to periodicals, including New Statesman, Listener, Guardian, Times Literary Supplement,and London Review of Books. Heaney's papers and letters are collected at Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

FURTHER READING

FURTHER READINGS ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

BOOKS

Allen, Michael, editor. Seamus Heaney, St. Martin's Press (New York, NY), 1997.

Andrews, Elmer, editor, The Poetry of Seamus Heaney: Essays, Articles, Reviews, Columbia University Press (New York, NY), 2000.

Beckett, Sandra L., editor, Transcending Boundaries: Writing for a Dual Audience of Children and Adults,Garland (New York, NY), 1999.

Bemporad, J., Seamus Heaney: Life and Works, Books Inc. (London, England) 1999.

Booth, James, editor, New Larkins for the Old: Critical Essays, St. Martin's Press (New York, NY), 2000.

Brown, Terence, Northern Voices: Poets from Ulster, Rowman & Littlefield (Totowa, NJ), 1975.

Burris, Sydney, The Poetry of Resistance, Ohio University Press (Athens, OH), 1990.

Buttel, Robert, Seamus Heaney, Bucknell University Press (Cranbury, NJ), 1975.

Concise Dictionary of British Literary Biography: Contemporary Writers, 1960 to the Present, Gale (Detroit, MI), 1992.

Contemporary Literary Criticism, Gale (Detroit, MI), Volume 5, 1976, Volume 7, 1977, Volume 14, 1980, Volume 25, 1983, Volume 37, 1986, Volume 74, 1993, Volume 91, 1996.

Corcoran, Neil,The Poetry of Seamus Heaney: A Critical Study, Faber (London, England), 1998.

Curtis, Tony, editor, The Art of Seamus Heaney, Wolfhound Press (Dublin, Ireland), 1994.

Deane, Seamus, Strange Country: Modernity and Nationhood in Irish Writing since 1790, Clarendon Press (Oxford, England), 1997.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 40: Poets of Great Britain and Ireland since 1960, Gale (Detroit, MI), 1985.

Duffy, Edna, The Subaltern Ulysses, University of Minnesota Press, 1994.

Durkan, Michael J., Seamus Heaney: A Reference Guide, G. K. Hall (New York, NY), 1996.

Fenton, James, The Strength of Poetry?, Oxford University Press (New York, NY), 2001.

Garratt, Robert F., Critical Essays on Seamus Heaney, G. K. Hall (New York, NY), 1995.

Goodby, John, Irish Poetry since 1950: From Stillness into History, University Press (Manchester, England), 2000.

Harmon, Maurice, editor, Image and Illusion: Anglo-Irish Literature and Its Contexts, Wolfhound Press, 1979.

Hensen, Michael, and Annette Pankratz, editors, The Aesthetics and Pragmatics of Violence, Stutz (Passau, Germany), 2001.

Kerridge, Richard, and Neil Samuels, editors, Writing the Environment: Ecocriticism and Literature, Zed (London, England), 1998.

Kiberd, Declan, Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation, J. Cape (London, England), 1995.

Kirkland, Richard, Literature and Culture in Northern Ireland since 1965: Moments of Danger, Longman (London, England), 1996.

Kirkpatrick, Kathryn. Border Crossings: Irish Women Writers and National Identities, University of Alabama Press (Tuscaloosa, AL), 2000.

Longley, Edna, Poetry in the Wars, Bloodaxe (Newcastle on Tyne, England), 1986.

Mahoney, John L., editor,Seeing into the Life of Things: Essays on Literature and Religious Experience, Fordham University Press (New York, NY), 1998.

Malloy, Catharine, and Phyllis Carey, editors, Seamus Heaney—The Shaping Spirit, University of Delaware Press (Newark, NJ), 1996.

McGuinness, Arthur E., Seamus Heaney: Poet and Critic, P. Lang (New York, NY), 1994.

Molino, Michael R., Questioning Tradition, Language, and Myth: The Poetry of Seamus Heaney, Catholic University of America Press (New York, NY), 1994.

Morrison, Blake, Seamus Heaney, Methuen (London, England), 1982.

O'Brien, Eugene, Seamus Heaney and the Place of Writing, Florida University Press (Gainesville, FL), 2002.

O'Brien, Eugene, Seamus Heaney: Creating Ireland of the Mind, Liffey Press (Dublin, Ireland), 2003.

Parini, Jay, editor, British Writers: Retrospective Supplement I, Scribner (New York, NY), 2002.

Roberts, Neil, editor, A Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry, Blackwell (Oxford, England), 2001.

Scott, Jamie S., and Paul Simpson-Housley, editors, Mapping the Sacred: Religion, Geography, and Postcolonial Literatures, Rodopi (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2001.

Stewart, Bruce, editor, That Other World, Smythe (Gerrards Cross, England), 1998.

Thomas, Harry, editor, Talking with Poets, Handsel (New York, NY), 2002.

Tobin, Daniel, Passage to the Center: Imagination and the Sacred in the Poetry of Seamus Heaney, University Press of Kentucky (Lexington, KY), 1999.

Vendler, Helen, Seamus Heaney, Harvard University Press (Cambridge, MA), 1998.

Viewpoints: Poets in Conversation with John Haffenden, Faber (London, England), 1981.

Welch, Robert, Changing States: Transformations in Modern Irish Writing, Routledge (London, England), 1993.

Wills, Clair, Improprieties: Politics and Sexuality in Northern Irish Poetry, Oxford University Press (Oxford, England), 1993.

PERIODICALS

America, August 3, 1996, p. 24; March 29, 1997, p. 10; October 11, 1997, p. 8; December 20, 1997, p. 24; July 31, 1999, John F. Desmond, "Measures of a Poet," p. 24; July 31, 1999, p. 24; April 23, 2001, p. 25.

American Scholar, autumn, 1981.

Antioch Review, spring, 1993; spring, 1999, p. 246.

Ariel, October, 1998, p. 7.

Atlantis, June, 2001, p. 7.

Back Stage, December 19, 1997, review of The Cure at Troy: A Version of Sophocles'"Philoctetes," p. 34.

Booklist, May 1, 1996, p. 1485; October 15, 1998, review of "Opened Ground," p. 388; February 15, 2000, Ray Olson, "A New Verse Translation," p. 1073; March 15, 2001, p. 1346; May 1, 2002, p. 1499.

Books for Keeps, September, 1997, p. 30.

Canadian Journal of Irish Studies, July, 1998, p. 51; December, 1998, p. 63.

Christian Scholar's Review, fall, 2001, p. 59.

Christian Science Monitor, April 22, 1999, Elizabeth Lund, "The Enticing Sounds of This Irishman's Verse," p. 20; February 3, 2000, "' Harry Potter' Falls to a Medieval Slayer," p. 1; April 13, 2000, p. 15; April 26, 2001, p. 19.

Classical and Modern Literature, spring, 1999, p. 243; fall, 2001, p. 71.

Commonweal, May 17, 1996, p. 10; November 6, 1998, p. 18; December 1, 2000, p. 22.

Contemporary Literature, winter, 1999, p. 627.

Contemporary Review, April, 2000, p. 206.

Critical Inquiry, spring, 1982.

Critical Quarterly, spring, 1974; spring, 1976.

Daily Telegraph (London, England), February 19, 2000, p. 116; March 31, 2001; April 13, 2002; May 5, 2003.

Dalhousie Review, autumn, 2000, p. 351.

Economist, September 12, 1998, review of Opened Ground, p. 14; November 20, 1999, "Translations of the Spirit," p. 101; June 23, 2001, p. 121.

Eire-Ireland, summer, 1978; winter, 1980; fall-winter, 2001, p. 7.

Encounter, November, 1975.

English, summer-autumn, 1997; summer, 1998, p. 111; summer, 2000, p. 143; summer, 2001, p. 149.

Essays in Criticism, April, 1998, p. 144.

Evening Standard, April 9, 2001, p. 47; April 8, 2002, p. 52.

Explicator, fall, 2002, p. 56.

Financial Times, March 21, 1998, p. 5; March 24, 2001, p. 4; March 30, 2002, p. 4; September 27, 2003, p. 26.

Globe and Mail (Toronto, Ontario, Canada), September 3, 1988.

Guardian (London, England), April 3, 1997, p. 9; October 9, 1999, p. 6; October 16, 1999, p. 10; October 18, 1999, p. 17; December 4, 1999, p. 11; January 19, 2000, p. 21; January 29, 2000, p. 3; September 30, 2000, p. 11; March 24, 2001, p. 12; April 7, 2001, p. 8; July 27, 2002, p. 21.

Harper's, March, 1981.

Harvard Review, fall, 1999, p. 74; fall, 2000, p. 12.

Independent (London, England), April 5, 1997, p. 7; December 1, 1997, p. 5; September 5, 1998, p. 17; September 8, 1998, p. 11; April 10, 1999, p. 5; October 2, 1999, p. 10; January 26, 2000, p. 5; January 29, 2000, p. 5; March 31, 2001, p. 10; June 16, 2001, p. 11; December 8, 2001, p. 9; February 19, 2003, p. 5; September 27, 2003, p. 33.

Independent on Sunday (London, England), April 6, 1997, p. 29; July 20, 1997, p. 32; November 9, 1997, p. 38; September 6, 1998, p. 10; March 21, 1999, p. 9; April 4, 1999, p. 11; October 10, 1999, p. 10; April 8, 2001, p. 46.

Irish Literary Supplement, fall, 1997, p. 14.

Irish Studies Review , spring, 1996; December, 2002, p. 303.

Irish Times (Dublin, Ireland), February 22, 2003, p. 61; April 12, 2003, p. 62; July 5, 2003, p. 57; July 12, 2003, p. 59; July 19, 2003, p. 55; August 2, 2003, p. 59; October 25, 2003, p. 55.

Irish University Review, spring-summer, 1998, pp. 56, 68; autumn-winter, 1999, p. 358.

Journal of Commonwealth and Postcolonial Studies, spring, 2000, p. 51.

Journal of Modern Literature, summer, 2000, pp. 471, 597; fall, 2001, p. 1.

Jouvert, fall, 1999, p. 40.

Kentucky Philological Review, March, 1998, p. 17.

Kenyon Review, winter, 2002, p. 160.

Kliatt, March, 1998, p. 57.

Library Journal, May 15, 1997, review of The Spirit Level, p. 120; September 1, 1997, review of The Spirit Level,p. 235; April 1, 1999, Barbara Hoffert, review of Opened Ground, p. 96; December, 1999, Thomas L. Cooksey, review of Beowulf, p. 132; August, 2000, p. 110; April 1, 2001, p. 104; April 1, 2002, p. 106; June 1, 2002, p. 155.

Listener, December 7, 1972; November 8, 1973; September 25, 1975; December 20-27, 1984.

Lit, October, 1999, pp. 149, 181.

Literature and Theology, March, 2003, p. 32.

London Review of Books, November 1-14, 1984; May 27, 1999, review of Opened Ground, p. 20.

Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1984; January 5, 1989; December 31, 2000, p. 6; April 22, 2001, p. 3.

Los Angeles Times Book Review, March 2, 1980; October 21, 1984; June 2, 1985; October 27, 1987; August 26, 1990; December 27, 1992.

Nation, November 10, 1979; December 4, 1995, p. 716; January 4, 1999, Jay Parini, review of Opened Ground, p. 25.

New Boston Review, August-September, 1980.

New Criterion, May, 2000, p. 31.

New Literary History, winter, 1999, p. 239.

New Republic, March 27, 1976; December 22, 1979; April 30, 1984; February 18, 1985; January 13, 1997, review of Homage to Robert Frost, p. 14; February 28, 2000, Nicholas Howe, "Scullionspeak," p. 32; February 28, 2000, p. 32.

New Statesman, April 25, 1997; September 18, 1998, review of Opened Ground, p. 54; April 15, 2001, p. 53.

Newsweek, February 2, 1981; April 15, 1985; February 28, 2000, Malcolm Jones, "'Beowulf' Brawling: A Classic Gets a Makeover," p. 68.

New Yorker, September 28, 1981; September 23, 1985; March 20, 2000, pp. 54, 56-66, 68, 79.

New York Review of Books, September 20, 1973; September 30, 1976; March 6, 1980; October 8, 1981; March 14, 1985; June 25, 1992; March 4, 1999, Fintan O'Toole, review of Opened Ground, p. 43; July 20, 2000, p. 18; November 29, 2001, p. 49; December 5, 2002, p. 54.

New York Times, April 22, 1979; January 11, 1985; November 24, 1998, Michiko Kakutani, review of Opened Ground; January 30, 1999, p. B11; January 20, 2000, Sarah Lyall, "Wizard vs. Dragon: A Close Contest, but the Fire-Breather Wins," p. A17; January 27, 2000, p. A27; February 22, 2000, Richard Eder, "Beowulf and Fate Meet in a Modern Poet's Lens," p. B8; March 20, 2000, Mel Gussow, "An Anglo-Saxon Chiller (with an Irish Touch)," p. B1; February 1, 2001, pB3, E3; April 20, 2001, p. B37, E39; May 27, 2001, p. AR19; June 2, 2001, p. A15, B9; September 30, 2002, p. B3, E3.

New York Times Book Review, March 26, 1967; April 18, 1976; December 2, 1979; December 21, 1980; May 27, 1984; March 10, 1985; March 5, 1989; December 14, 1995, p. 15; June 1, 1997, p. 52; December 20, 1998, review of Opened Ground, p. 10; June 6, 1999, review of Opened Ground, p. 37; February 27, 2000, James Shapiro, "A Better 'Beowulf'" p. 6; December 3, 2000, p. 9; April 8, 2001, p. 16; April 29, 2001, p. 22; June 3, 2001, p. 24; October 6, 2002, p. 33.

New York Times Magazine, March 13, 1983.

Nexos, July, 1999, p. 83.

Observer (London, England), March 23, 1997, p. 16; January 4, 1998, p. 15; September 6, 1998, review ofOpened Ground, p. 17; November 7, 1999, p. 8; January 23, 2000, p. 11; September 10, 2000, p. 16; April 15, 2001, p. 15; April 7, 2002, p. 13.

Papers on Language and Literature, spring, 2001, p. 205.

Parnassus, spring-summer, 1974; fall-winter, 1977; fall-winter, 1979.

Partisan Review, number 3, 1986; fall, 1997, p. 674.

Philosophy and Literature, October, 2002, p. 405.

Poetry, June, 1992; December, 2000, p. 211; February, 2002, p. 296.

Princeton University Library Chronicle, spring, 1998, p. 559.

Publishers Weekly, April 29, 1996, p. 63; January 27, 1997, p. 14; November 2, 1998, review of Opened Ground,p. 74; February 7, 2000, Jana Riess, "Heaney Takes U.K.'s Whitbread Prize," p. 18; February 14, 2000, Judy Quinn, "Will Readers Cry 'Wulf'?," p. 86; February 21, 2000, review of Beowulf, p. 84; March 13, 2000, Daisy Maryles, "A Real Backlist Mover," p. 22; August 14, 2000, p. 349; September 4, 2000, p. 44; February 19, 2001, p. 87.

Saturday Review, July-August, 1985.

Sewanee Review, winter, 1976; April-June, 1998, p. 184.

South Carolina Review , fall, 1999, pp. 119, 132.

Southern Review, January, 1980; spring, 2000, p. 418; spring, 2002, p. 358.

Spectator, September 6, 1975; December 1, 1979; November 24, 1984; June 27, 1987; September 16, 1995, p. 39; September 5, 1998, review of Opened Ground, p. 36; April 6, 2002, p. 32.

Sunday Times (London, England), September 6, 1998, p. 7; October 3, 1999, p, 4; October 17, 1999, p. 41; February 6, 2000, p. 18; October 1, 2000, p. 46; December 10, 2000, p. 16; April 1, 2001, p. 35; April 14, 2002, p. 34; April 13, 2003, p. 49.

Symbiosis, April, 1999, p. 63; October, 2002, p. 133.

Time, March 19, 1984; February 25, 1985; October 16, 1995; March 20, 2000, Paul Gray, "There Be Dragons: Seamus Heaney's Stirring Translation of Beowulf Makes Waves on Both Shores of the Atlantic," p. 84.

Times (London, England), October 11, 1984; January 24, 1985; October 22, 1987; June 3, 1989; September 11, 1998, p. 21; October 29, 1998, p. 44; March 27, 1999, p. 16; September 23, 1999, p. 42; October 26, 1999, p. 50; May 20, 2000, p. 19; April 4, 2001, p. 15; April 17, 2002, p. 21; July 2, 2003, p. 2.

Times Educational Supplement, November 7, 1997, p. 2; September 11, 1998, review of Opened Ground, p. 11.

Times Literary Supplement, June 9, 1966; July 17, 1969; December 15, 1972; August 1, 1975; February 8, 1980; October 31, 1980; November 26, 1982; October 19, 1984; June 26, 1987; July 1-7, 1988; December 6, 1991; October 20, 1995, p. 9.

Tribune Books (Chicago, IL), April 19, 1981; September 9, 1984; November 8, 1987; November 25, 1990.

Twentieth Century Literature, fall, 2000, p. 269.

Twentieth-Century Studies, November, 1970.

U.S. News and World Report, March 20, 2000, Brendan I. Koerner, "Required Reading," p. 68.

Variety, May 4, 1998, Markland Taylor, review of "The Cure at Troy," p. 96.

Virginia Quarterly Review, autumn, 1992.

Wall Street Journal, April 2, 1999, review of Opened Ground, p. W6; February 24, 2000, Elizabeth Bukowski, "Seamus Heaney Tackles Beowulf," p. A16; March 10, 2000, "Slaying Dragons," p. W17.

Washington Post Book World, January 6, 1980; January 25, 1981; May 20, 1984; January 27, 1985; August 19, 1990.

Washington Times, November 29, 1998, p. 6; February 6, 2000, p. 8; June 9, 2002, p. B08.

World Literature Today, summer, 1977; autumn, 1981; summer, 1983; autumn, 1996, p. 963; summer, 1999, p. 534; autumn, 2000, p. 247; winter, 2001, p. 119; winter, 2002, p. 110.

ONLINE

Biblio, http:// www.biblio-india.com/ (November-December, 2000).

Interviews with Poets, http://www.interviews-with-poets.com/ (March 26, 2004).

![]()

.jpg)