|

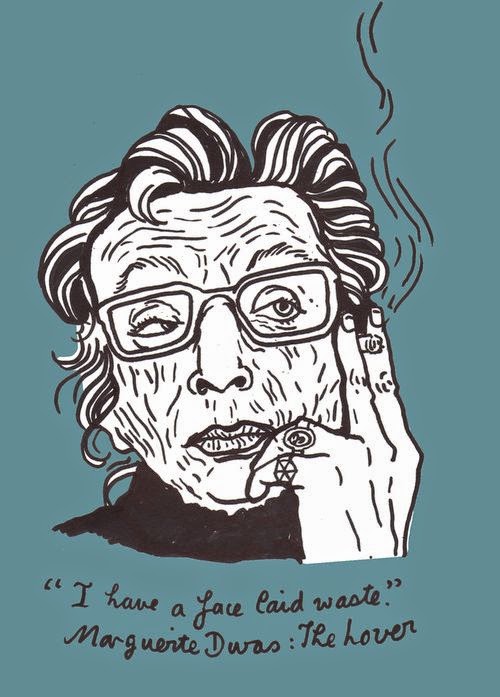

| Marguerite Duras |

DRAGON

DE OTROS MUNDOS

PESSOA

Marguerite Duras / O amante da China do Norte

Marguerite Duras / O amor

Marguerite Duras / A doença da morte

RIMBAUD

Marguerite Duras / La voix et la passion

Florence Bouchy / Les enfants de Marguerite Duras

Marguerite Duras est-elle un «grand écrivain»?

Marguerite Duras / O amor

Marguerite Duras / A doença da morte

Marguerite Duras /Dez horas e meia numa noite de verão

Marguerite Duras / É tudo

Enrique Vila-Matas / Marguerite Duras

Marguerite Duras / É tudo

Enrique Vila-Matas / Marguerite Duras

RIMBAUD

Marguerite Duras / La voix et la passion

Florence Bouchy / Les enfants de Marguerite Duras

Marguerite Duras est-elle un «grand écrivain»?

Marguerite Duras

Marguerite Donnadieu

(1914 - 1996)

French novelist, representative of the nouveau roman, scenarist, playwright, and film director, internationally known for her screenplays ofHiroshima Mon Amour , directed by Alain Resnais, and India Song (play 1973, screenplay 1975). After relatively traditional novels and stories, Duras published in 1958 the novel Moderato Cantabile, which first summarized her themes of sexual desire, love, death, and memory. However, Duras did not publish a manifesto of her ideas like so many representatives of the noveau roman did, but her final work, Ecrite (1995, Writing), gave a brief account of her life and theory of writing.

"The solitude of writing is a solitude without which writing could not be produced, or would crumble, drained bloodless by the search for something else to write. When it loses its blood, its author stops recognizing it. And first and foremost it must be never be dictated to a secretary, however capable she may be, nor ever given to a publisher to read at that stage." (from Writing, transl. by Mark Polizzotti, 1998)

Marguerite Duras was born in Gia Dinh, Indochina (now Vietnam). Her father died on sick leave in France when she was four, and her mother, a teacher, struggled hard to bring up her three children. Duras spent most of her childhood in Indochina. While still a teenager, she had an affair with a wealthy Chinese man, whom she called Monsieur Jo and also Léo. Later Duras returned to this period in her books. At the age of 17, she moved to France, where she studied law and political science at the Sorbonne, graduating in 1935. Duras took her penname from the name of a village in France near where her father had owned property.

From 1935 to 1941 Duras worked as a secreraty at the ministry of colonies. During World War II, she was a member of French Resistance; she had also joined the Communist Party. After the war she condemned its policies and was expelled in 1950 for revisionism. Although Duras had helped writers opposing Nazis during the war, she was also accused of being a member of a literary committee controlled by the Germans.

Duras's husband Robert Antelme was a member of the resistance group Richelieu, led by François Mitterrand. Antelme was captured by the Gestapo, but he survived Buchenwald, Gandersheim, and Dachau. After returning to France, Antelme wrote his memoirs, L'espece humaine. Duras, who had planned to leave Antelme, nursed him. This period was the basis for Duras's collection of short stories, entitled La Douleur (1985). Her first book, Les Impudents, came out in 1942. Her early novels were influenced by Ernest Hemingway, Virginia Woolf, and François Mauriac.

Duras worked as a journalist for the magazine Observateur. Her reputation was made in the 1950s with such works as Un barrage contre le Pacifique (1950), which depicted a poor French family in Indochina, the psychological romantic novel Le marin de Gibraltar (1952), and Le Square (1955), which associated her with the New Novel group. Unlike other avant-garde writers, Duras was not so much interested in abstract literary theories than examining the power of words, remembering, forgetting, and feelings of alienation. Often her dialogue is elliptical and instead of describing action she focuses on the inner life of her characters.

The theme of love between people of different races runs through many of Duras's works, among them Hiroshima, Mon Amour, about the brief love affair between a married French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) and a Japanese architect (Eiji Okada). Riva tells Okada about her forbidden love affair with a German soldier during the occupation. After the Liberation her hair was shorn by the villagers and she had a mental breakdown. The film is famous for its innovative use of flashback and parallel montage. In Japan it did poor business under the titleTwenty-four Hour Love Affair. Love, especially in Duras's earlier work, offers her characters a way to escape their aimlessness of life. Other ways are alcohol or "madness".

Hiroshima, Mon Amour received an Academy Award nomination for Best Screenplay. All reviews were not enthusiastic. "That a film so amateur should receive so much critical acclaim is a sad commentary on the state of Western culture... the enthusiasms of a-political critics for this picture reveals a mental confusion so close to intellectual bankruptcy as to alarm everyone who believes the West has a mission."(H.H., Films in Review, June/July 1960) Duras was also accused of ignoring Okada's story, and drawing parallels between the Hiroshima holocaust and Riva's suffering. After the May 1968 students' revolt, Duras's writing grew increasingly abstract. Although she rejected the aesthetic and stylistic techniques in her earlier work, she returned to this material to turn it into new plays, novels and films. Duras's sparse, yet suggestive style, and her use of language, was much discussed by feminists as embodying feminine writing.

"When a woman drinks it's as if an animal were drinking, or a child. Alcoholism is scandalous in woman, and a female alcoholic is rare, a serious matter. It's a slur on the divine in our nature. I realized the scandal I was causing around me. But in my day, in order to have the strength to confront it publicly – for example, to go into a bar on one's own at night – you needed to have had something to drink already."

(from Practicalities, 1990)

|

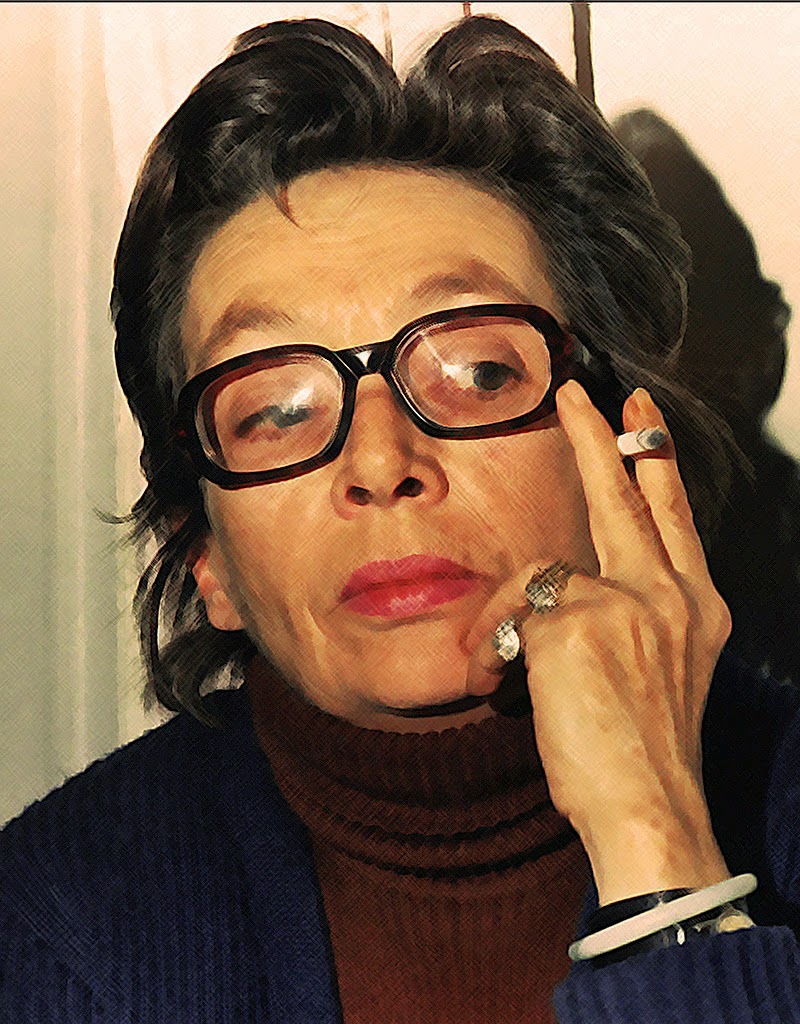

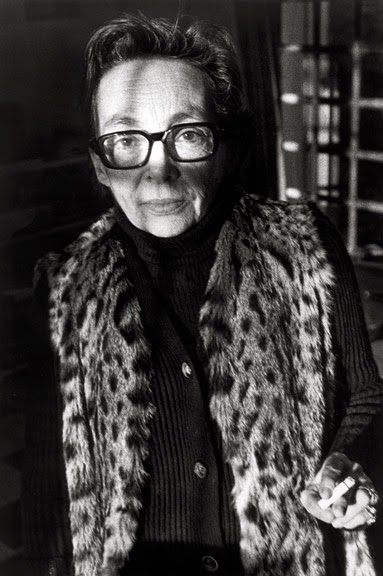

| Marguerite Duras Photo by Ralph Gibson |

The Lover was made in 1992 into a film, directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud. "Destruction. A key word when it comes to Marguerite Duras, who uses her novels, her plays and her films to study herself in as many mirrors; she identifies herself with her work to the point that she no longer knows what is autobiographical fact and what is fiction." (Jean-Jacques Annaud, CNN, March 5, 1998) The film, in which a teenage girl is initiated into sex by an older Chinese dandy, was available in Europe in a sexier version. In L'Amant de la Chine du Nord (1990) she again returned to her Vietnamese experience.

Duras's life in the 1980s and 1990s was subject for Yann Andréa Steiner's books M.D. (1983) and Cet Amour-lá (1999). They give an account of Duras's later creative period, which was shadowed by her drinking. Andréa, who was 38 years younger than Duras, became obsessed with her books, and met her in 1980. Andréa worked as her secretary, and also acted in her films. Their relationship was tumultuous: "I don't know who you are," she could say and drive him out of her apartment, but he always returned. In Practicalities (1987) Duras tells about her life with Andréa, and confesses that she became an alcoholic immediately when she started to drink. Duras also mentions that she took aspirin every day for fifteen years. Yann Andréa encouraged her to go to hospital for treatment. Duras went in October 1982 to the American Hospital of Paris. After returning back home, she believed her apartment was full of strange people. Yann tried to confirm her that there was nobody else in the apartment. To please her he once opened and closed a door for one of Duras's hallucinatory guests. Duras lived with Andréa until her death in Paris on November 3, 1996.

Marguerite Duras

Critical Biography written by: Ashley Finch

Critical Biography based on: Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994.

Critical Biography

Marguerite Duras was famous for her work as a French writer, a film director, and her battle with alcoholism. But in her memoirs, she doesn't discuss her experiences with writing, film, or her devastating battle with alcoholism. Instead, she focuses on her experiences during World War II. There are two stories in particular that she spends a lot of time talking about in her collections of memoirs, an autobiographical essay from her time working with the PCF, Parti communiste francais, and another that encompasses both the time she spent waiting for her husband, Robert Anthelme, to return from the war and the time it took to nurse him back to health from the typhus that he contracted while he was held prisoner by the Germans in Bergen-Belsen holding camp. These two stories, while important for gaining a deeper insight into the events surrounding World War II in France, are also important for understanding gender roles that were taken on during this time period. Through Duras’ two main memoirs, which are contained within War: The Memoir, we can see that although she adopted some practices that were typical of a wife in the 1940’s (e.g. nursing her sick husband back to health after the war, waiting for him to return with bated breath, working a secretarial job during the war), she also actively defied the stereotypical gender roles for women during her time period (e.g. divorcing her husband to marry his best friend, actively participating in the French Resistance).

Her most widely known memoir, and the one that I will address first, is entitled The War. This memoir was written during the time that Marguerite Duras spent waiting for her husband to return from Bergen-Belsen holding camp, it encompasses her horrors nursing him back to health from a bout of typhus and her subsequent request for a divorce after he recovered from typhus and regained some of his strength. This was also the first, and primary, story contained within her compilation, The War: A Memoir. Even though this story is chronologically the last rather than the first that Duras wrote, it is important to address this particular memoir first in order to obtain a clear understanding of Marguerite Duras: her courage, her stability, and her endurance. She chose to place this story first in her memoir compilation and I will stay true to that format with this critical biography in an attempt to accurately describe her life in the order that she wanted it told.

After men returned from the war, their wives were expected to take care of them and Marguerite Duras fulfilled this duty willingly, but after conforming so typically to those expected gender roles she shook things up completely by divorcing her husband as soon as he was well again and almost immediately after her returned from Bergen-Belsen.

Bergen-Belsen was not an extermination camp like Auschwitz or Majdanek. [1] The prisoners in Bergen-Belsen didn’t die by way of gas chambers, torture, shooting, or medical experiments. Instead, starvation, disease epidemics, and general neglect killed the thousands of prisoners who died at Bergen-Belsen. Marguerite Duras’ husband was also affected by the disease epidemics. He was almost a casualty of the typhus [2] that he contracted while he was a political prisoner in Bergen-Belsen. He was so sick that when they brought the doctor in to see him after his return to France, he didn’t immediately recognize that the body he saw was living. “And then he realized: the form wasn’t dead yet, it was hovering between life and death, and he, the doctor, had been called in to try to keep it alive.” [3] Despite Anthelme's near-death state, Duras slowly nursed him back to health.[4] She was the perfect wife, despite the fact that that may not have been her ultimate goal. Even though she clearly did not feel as a wife to Anthelme, she deeply cared about him. She helped him get to the bathroom because of his dysentery, she spoon-fed him gruel when he couldn’t eat anything else for fear of it killing him, and she prepared meal after meal for him when he finally was healthy enough to eat solid food. On the surface, it appeared as though she conformed perfectly to her role as a wife, even though it was difficult, and at times almost impossible. And then she told him that she wanted a divorce. [5] She deeply cared for Robert Anthelme, as a close friend and confidante, but she no longer cared for him as a wife cares for a husband. For that reason, she had loved him enough to nurse him back to health after the war (a clearly difficult feat), but she did not want to stay married to him.

It is safe to say that her decision to request a divorce from her husband almost immediately after he recovered from his near-death experience with typhus and days after he received the news that his sister had died during the war was not typical. She writes, “Another day I told him we had to get a divorce, that I wanted a child by D. … I said that even if D. hadn’t existed I wouldn’t have lived with him again.”[6] If Marguerite Duras had been fulfilling traditional gender roles, she would not have left her husband. She would not have requested a divorce. She would not have left him for a man that she describes as his “best friend.”[7] Instead, she would have stayed married to Anthelme, especially since she loved him enough to nurse him back to health.

The divorce is only one way that Marguerite Duras pushed the boundaries of gender roles during World War II, there are other instances of her gender defiance in The War. Before she recounts the story of Robert Anthelme coming home, she tells the story of her own suffering while he was gone. On the one hand she is a loving wife who spends her time reading lists of names of soldiers that have been brought home from the war and those who have perished in it (an activity that she describes as common for wives who had family in the war). She waits patiently for her husband to return home and seeks the assistance of a close male friend (the one she would eventually leave her husband for) for support during Anthelme’s absence. On the other hand, she had enough courage to start a newspaper in September 1944 called Libres [8] in order to communicate information about movements of prisoners to their family and friends. Though she was participating in classic "women's work" like writing for families, she still pushed boundaries by using forged papers and sheer diligence to get access to the information that she needed to publish her newspaper. One day she was told that she couldn’t stay and talk to the prisoners at the Gare d’Orsay because the rules didn’t allow unofficial services at the train station. She responded, “That’s not a good enough reason.” [9] and proceeded to slip in to a line of prisoners in order to obtain information. She was also told that her work with the newspaper and her publishing of “Nazi atrocities” [10] was “dangerous” [11], but she pressed on until the war was over and she had to focus on nursing her sick husband back to health.

Marguerite Duras made it clear through this memoir that, though she was constantly in emotional and mental anguish over the imprisonment of her husband, she was a strong woman. She had to have been strong to keep up a newspaper that reported on dangerous issues like Nazi war crimes and emotionally involved stories of lost family members. But, after reading the next memoir in her compilation, entitled Monsieur X, Here Called Pierre Rabier, and understanding her often dangerous position in the French Resistance it is easy to see that, though it may not have been the common thing to do, she was a strong woman both in the beginning of the war and at the end.

In the preface of this memoir, Duras makes it abundantly clear that she feels this memoir is important for the description of Rabier as a human being solely intended for dispensation of reward and punishment. She saw him as subhuman, not capable of the same emotions that other human beings were capable of. This description makes it easier to understand how some of the men who carried out punishment in the Nazi party may have acted and how others reacted to their cold nature. She writes, “They [her friends] decided it ought to be published because of the description of Rabier” [12] However, in my opinion the memoir is important for another reason. It is an important memoir because of the description of Marguerite Duras herself.

When Marguerite Duras wrote Monsieur X, Here Called Pierre Rabier, she was involved in the “vast and complex network” that was the French Resistance.[13] Whether she knew it or not, she was involved in a group encompassing more than 400,000 people, most of whom were men. [14] The Germans had recently captured her husband and Duras was still under the impression that if she sent him packages, he would be able to obtain them. Her initial meeting with Rabier was an attempt to send Anthelme a food parcel. She was unable to obtain a parcel permit and her only hope of getting him the parcel was via a German examining officer. She had hope that Rabier would be her key to delivering the parcel to her husband. This was the beginning of her tumultuous relationship with Rabier. Rabier was part of the Gestapo and Duras was an active part of the French Resistance, along with her arrested husband. During every meeting with Rabier, she expressed at the very least the knowledge that he could arrest her and at the most a fear that he would arrest her and punish her husband and her comrades for their affiliation with her.

But their meetings continued. At this time, Marguerite Duras was in close contact with Francois Morland, a member of the resistance who created a network of spies during the war and was the mastermind behind getting his good friend and fellow resistance member Robert Anthelme home safe, though incredibly ill, from Bergen-Belsen. Morland demanded the Duras stay in close contact with Rabier. [15] Despite the incredible risk and danger involved with her meetings with him, she continued to attend them. She was driven by a motivation to help the resistance, but more importantly she was encouraged by the connection that Rabier allowed her to have with her husband. Rabier was the only link between Duras and Anthelme. Even though Duras was planning to divorce her husband when he got back from the war, she still conformed to traditional gender roles by expertly maintaing her only link to her husband. But her relationship with Rabier not only assisted in maintaining a link with her husband, it also facilitated her advancement in the French resistance.

The typical woman would not have been such a strong figure in the resistance; she would not have acted as a spy during a war when blowing her cover would have meant imprisonment or death. Duras even goes so far as to promise Morland that she would help in the initiative to kill Rabier. [16] Her strength of character is astounding as is the level of trust that Francois Morland and the other resistance members have for her. Though males were dominating the French Resistance because they were “…people who, when captured, usually stood up under torture” [17], Marguerite Duras was obviously considered strong enough to endure the punishment that she could have received it she would have been caught by Rabier. This is incredible because it shows how important she was to the resistance and how much the men in the resistance trusted her, even though she was a woman. Given the fact that she doesn’t seem to find this important (she focuses more on Rabier’s nature than her spy status), this might suggest that women had a larger role in the resistance than historians’ previously thought.

Marguerite Duras was clearly an important (albeit minor) figure in both the French Resistance and in World War II in terms of how women's roles during that time period are understood. As I have already stated, Duras did not conform to stereotypical gender roles during World War II. In fact, she was highly atypical. Though she did nurse her sick husband back to health, which would have been a typical woman’s job after the war, her other roles in the war and its aftermath were much different. During the war, she was an integral member of the resistance and she even plotted with other resistance members about the assassination of a member of the Gestapo. She worked as a spy for a brief time. She started her own newspaper that addressed controversial issues like Nazi war crimes. Then after the war, she told her husband that she wanted a divorce almost immediately after he was cured of typhus. Finally, years after her experiences in World War II, she became a critically acclaimed author of novels, plays, films, and short narratives. Through her memoirs, it becomes clear that some women, like Duras, strayed from traditional gender roles during World War II and were integral to the success of initiatives like the French resistance.

Notes and References

↑ Rosensaft, Menachem. "The Mass Graves of Bergen-Belsen: Focus for Confrontation." Jewish Social Studies 41 (1979): 158.

↑ Bayne-Jones, S. "Typhus." The American Journal of Nursing 44 (1944): 821-3.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 55.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 57-62.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 63.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 63.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 63.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 11.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 11.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 13.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 13.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 72.

↑ Wright, Gordon. "Reflections on the French Resistance (1940-1944)." Political Science Quarterly 77 (1962): 337.

↑ Wright, Gordon. "Reflections on the French Resistance (1940-1944)." Political Science Quarterly 77 (1962): 338.

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 79

↑ Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994: 81.

↑ Wright, Gordon. "Reflections on the French Resistance (1940-1944)." Political Science Quarterly 77 (1962): 339.

Annotated Bibliography

1. Duras, Marguerite. The War: A Memoir. Translated by Barbara Bray. London: The New Press, 1994.This book is the initial autobiography that describes Marguerite Duras' experiences with the war. She explains everything in great detail, from her excruciating experience waiting for her husband while he was at Bergen-Belsen to her own hardships living in France during the war. This autobiography is important for understanding the burdens that many people suffered while living "free" in cities that were occupied by the Nazis and waiting for their loved ones to come home. It provides a different perspective on the suffering that Nazi occupation caused, which is important to understanding the vast suffering caused by the war.

2. Duras, Marguerite. Wartime Writings:1943-1949. Translation by Linda Coverdale. London: The New Press, 2008.This book provides another, similar autobiography that can be compared with The War: A Memoir. Since the stories written are also about Marguerite Duras' life and her involvement in the war, they provide new and interesting insight into areas that were not fully covered by her initial autobiography. They also happen to be clearer and easier to read than her other memoirs, so they paint a less emotional, but more detailed picture of her experience in the war. This book is important for understanding more fully the life of Marguerite Duras and her experiences within the context of World War II.

3. Bayne-Jones, S. "Typhus." The American Journal of Nursing 44 (1944): 821-3.This article addresses the different types of typhus, the germs that cause typhus, and the symptoms of typhus fever. The author successfully explains the different stages of the disease, from onset to potential fatality. Since Marguerite Duras extensively explains her husband's bout of typhus in her autobiography, it is important to understand the process of the disease. This assists in better comprehension of the magnitude of typhus that her husband suffered from as well as a more complete understanding of the breadth of disease at concentration camps.

4. Rosensaft, Menachem. "The Mass Graves of Bergen-Belsen: Focus for Confrontation." Jewish Social Studies 41 (1979): 155-186.This article examines the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen by discussing the kinds of people that were kept at Bergen-Belsen in addition to the way that people were treated while they were alive, and how many eventually died in the camp. This is the camp where Marguerite Duras' husband was housed and eventually returned from, debilitated by typhus. This article is important for understanding the kind of camp where her husband was kept and the atrocities that occurred there.

5. Ross, George. "Party Decline and Changing Party Systems: France and the French Communist Party." Comparative Politics 25 (1992): 43-61.This article talks about the French Communist Party and the affect it had on France during World War II. In her memoirs, Duras writes extensively about her involvement in the PCF, or Parti Communiste Francais. This article gives insight into how the PCF functioned, what their goals where, and their eventual decline. It is important to understand the influence that the PCF had both within and without France in order to completely understand Duras' memoirs.

6. Wright, Gordon. "Reflections on the French Resistance (1940-1944)." Political Science Quarterly 77 (1962): 336-49.

This article is a summary of the French Resistance, from 1940-1944. Both Marguerite Duras and her husband, Robert Anthelme, were connected to the French Resistance and Anthelme's connection with this politically motivated group was what eventually sent him to Bergen-Belsen. This article is important to understanding Marguerite Duras and her husband's political ideals and their motivations during the war.

For further reading: Marguerite Duras by Alfred Cismaru (1971); Marguerite Duras by A. Vircondelet (1972); Marguarite Duras: Modersto Cantabile by David Coward (1981); Alienation and Absence in the Novels of Marguerite Duras by Carol J. Murphy (1982); M.D. By Yann Andréa Steiner (1983): Marguerite Duras: Writing on the Body by Sharon Willis (1987); The Other Woman: Feminism and Feminity in the Works of Marguerite Duras by Trista Selous (1988); Remains to Be Seen: Essays on Marguerite Duras, ed. by Sanford Scribner Ames (1988);Women and Discourse in the Fiction of Marguerite Duras by S.D. Cohen (1993); Duras: A Biography by A. Vircondelet (1994); Marguerite Duras by Laure Adler (Gallimard, 1998); Cet Amour-lá by Yann Andréa (1999); Marguerite Duras: A Life by Laure Adler (2001) Nouveau roman, see also Claude Simon, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Michel Butor and Nathalie Sarraute. "...De ce dialogue harassant, il se dégage bien quelques petites choses; le désarroi de cette femme, la tristesse de sa vie, un vague désir de communiquer, par-delà les mots, avec quelqu'un – et pourquoi pas, après tout, avec ce Chauvin qui s'est trouvé là? Mais pourquoi ces saouleries au vin rouge? Ce brusque désir de rompre avec la vie normale? Il y a une sorte d'outrance qui fait que le lecteur ne peut, derrière ce comportement qu'on nous dit, imaginer qu'un monde superficiel dans lequel vit un être superficiel. Cette coquille de noixque Marguerite Duras nous offre ne ressemble en rien à celle dont parlait Joyce lorsqu'il disait vouloir mettre all space in a nutshell, car elle est, au départ, aussi faussement bariolée qu'un œuf de Pâques." (Anne Villelaur about Moderato Cantabile in Les Lettres françaises, 6-3-1958)

Selected works:

- Les Impudents, 1942

- La Vie tranquille: roman, 1944

- Un barrage contre le Pacifique: roman, 1950- The Sea Wall (translated by Herma Briffault, 1967) / A Sea of Troubles (translated by Antonia White, 1969)- film 2008, dir. by Rithy Panh, starring Gaspard Ulliel, Vincent Grass, Isabelle Huppert, Lucy Harrison

- Le Marin de Gibraltar: roman, 1952- The Sailor from Gibraltar (translated by Barbara Bray, 1967)- film 1966, dir. by Tony Richardson; script by Christopher Isherwood, Don Magner, Tony Richardson

- Les Petits Chevaux de Tarquinia: roman, 1953- Little Horses of Tarquinia (translated by Peter DuBerg, 1985)

- Des journées entières dans les arbres, 1954 (stage adaptation: Days in the Trees)

- Le Square: roman, 1955- The Square (translated by Sonia Pitt-Rivers and Irina Morduch, 1959)

- Le Square, 1957 (produced; with Claude Martin)

- Moderato cantabile, 1958- Moderato Cantabile (translated by Richard Seaver, 1960)- Moderato Cantabile. Sonaatti rakkaudelle (suom. Marita Hietala, 1967)- film 1960, dir. by Peter Brook, screenplay with Gérard Jarlot and Peter Brook, starring Jeanne Moreau, Jean-Paul Belmondo and Pascale de Boysson

- Hiroshima mon amour: scénario et dialogues, 1959 (filmscript)- film prod. Argos Films, Como Films, Daiei Studios, dir. by Alain Resnais, starring Emmanuelle Riva, Eiji Okada, Stella Dassas, Pierre Barbaud- Hiroshima Mon Amour (translated by Richard Seaver, 1961)- Hiroshima, rakastettuni (suom. Kristina Haataja, 1990)

- Les Viaducs de la Seine-et-Oise, 1960 (stage adaptation: The Viaducts)

- Dix heures et demie du soir en été, 1960- Ten-Thirty on a Summer Night (translated by Anne Borchardt, 1962)- film 10:30 P.M. Summer, 1963, dir. by Jules Dassin, starring Melina Mercouri, Romy Schneider, Peter Finch

- Une aussi longue absence: scénario et dialogues, 1961 (screenplay, with Gérard Jarlot)- film 1962, dir. by Henri Colpi, starring Alida Valli, Georges Wilson, Charles Blavette

- Les Papiers d'Aspern, 1961 (with Robert Antelme, adaptation of the play The Aspern Papers by Michael Redgrave, based on the story by Henry James)

- Miracle en Alabama, 1961 (with Gérard Jarlot, adaptation of The Miracle Worker by William Gibson)

- L'Après-midi de Monsieur Andesmas, 1962- The Afternoon of Monsieur Andesmas (in Four Novels: The Square; Moderato Cantabile; Ten-Thirty on a Summer Night; The Afternoon of Mr. Andesmas, introd. by Germaine Brée, 1965)- film 2004, dir. by Michelle Porte, starring Michel Bouquet, Miou-Miou, Paloma Veinstein

- La bête dans la jungle, 1962 (with James Lord, from The Beast in the Jungle by Henry James)

- Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein, 1964- The Rapture of Lol V. Stein (translated by Eileen Ellenbogen, 1967) / The Ravishing of Lol Stein (translated by Richard Seaver, 1967)- Lol V. Steinin elämä (suom. Annikki Suni, 1986)

- Sans merveille de Michel Mitrani, 1964 (television play, with Gérard Jarlot)

- Four Novels: The Square. Moderato Cantabile. Ten-Thirty on a Summer Night. The Afternoon of Mr. Andesmas, 1965 (translated by Sonia Pitt-Rivers, et al.)

- Les Eaux et Forêts, 1965 (produced)

- Théâtre I, 1965

- Des journées entières dans les arbres, 1965 (produced)

- La Musica, 1965 (produced)- TV film, in Love Story, 1965, prod. Associated Television (ATV), dir. John Nelson-Burton, starring Rosalind Atkinson, Michael Craig and Edward Higgins

- 10:30 P.M. Summer, 1966 (screenplay, with Jules Dassin)- film 1966, prod. Argos Films, Jorilie, dir. Jules Dassin, starring Melina Mercouri, Romy Schneider and Peter Finch

- La Musica, 1966 (director, with Paul Seban; screenplay)- film 1967, prod. Les Films Raoul Ploquin, Les Productions Artistes Associés, starring Delphine Seyrig, Robert Hossein, Julie Dassin

- Les Rideaux blancs de Georges Franju et Tadeusz Konwicki, 1966 (screenplay)

- Le Vice-Consul, 1966- The Vice-Consul (translated by Eileen Ellenbogen, 1968)- Varakonsuli (suom. Mirja Bolgár, 1988)

- Three Plays, 1967 (translated by Barbara Bray and Sonia Orwell)

- L'Amante anglaise, 1967- Amante Anglaise (translated by Barbara Bray, 1968)- Pään salaisuus: kuunnelma (suom. Saara Palmgren, 1987)

- Théâtre II, 1968

- Le Shaga, 1968 (produced; dir.)

- Yes, peut-être, 1968 (produced)

- Détruire, dit-elle, 1969 (director, screenplay)- Destroy, She Said (transl. by Barbara Bray, 1970)- film 1969, prod. Ancinex, Madeleine Films, starring Catherine Sellers, Michael Lonsdale, Henri Garcin

- La Danse de mort, d'après August Strindberg, 1970 (prodeced)

- Abahn Sabana David, 1970

- L'Amour, 1971

- Jaune le soleil, 1971 (director, screenplay)- film 1972, prod. Albina Productions S.a.r.l., starring Catherine Sellers, Sami Frey, Dionys Mascolo

- Ah! Ernesto, 1971 (with Bernard Bonhomme)

- Nathalie Granger, 1972 (director, screenplay)- film 1973, starring Lucia Bosé, Jeanne Moreau, Gérard Depardieu, Luce Garcia-Ville

- India Song, 1973 (play, screenplay in 1975)- India Song (transl. by Barbara Bray, 1976)

- Home, 1973 (from the play by David Storey)

- La ragazza di passaggio / La Femme du Gange / Woman of the Ganges, 1973 (director, screenplay)- film: La Femme du Gange, 1974, starring Catherine Sellers, Christian Baltauss, Gérard Depardieu, Dionys Mascolo

- Nathalie Granger, suivi de La Femme du Gange, 1973

- Le navire Night, 1974- LaivaNuit (suom. Kristina Haataja, 1994)

- Les Parleuses, 1974 (interviews)- Woman to Woman (translated by Katharine A. Jensen, 2004)

- Ce que savait Morgan, 1974 (screenplay, with others)

- Suzanna Andler; La musica & L'amante anglaise, 1975

- India Song, 1975 (director, screenplay)- India Song (suom. Kristina Haataja, 1999)- film 1975, starring Delphine Seyrig, Michael Lonsdale, Mathieu Carrière, Claude Mann

- Étude sur l'oeuvre littéraire, théâtrale, et cinématographique, 1975 (with Jacques Lacan and Maurice Blanchot)

- Des journées entières dans les arbres, 1976 (director, screenplay)- Whole Days in the Trees (translated by Anita Barrows, 1984)- film 1976, starring Madeleine Renaud, Bulle Ogier, Jean-Pierre Aumont, Yves Gasc

- Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta désert, 1976 (director, screenplay)- film 1976, starring Nicole Hiss, Michael Lonsdale, Sylvie Nuytten, Delphine Seyrig

- Territoires du féminin, 1977 (with Marcelle Marini)

- L'Éden Cinéma, 1977 (produced)

- Le Camion, suivi d’entretiens avec Michelle Porte, 1977 (director, screenplay)- film 1977, prod. Auditel, Cinéma 9, starring Marguerite Duras, Gérard Depardieu

- Baxter, Vera Baxter, 1977 (director, screenplay)- film 1977, starring Delphine Seyrig, Noëlle Chatelet, Nathalie Nell, Claude Aufaure, Gérard Depardieu

- Les Mains négatives, 1978 (director, screenplay)

- Le Navire Night, 1978 (director, screenplay)- film 1979, prod. Les Films du Losange, starring Dominique Sanda, Bulle Ogier, Mathieu Carrière

- Les Lieux de Marguerite Duras, 1978 (interview, with Michelle Porte)

- Le Navire Night et autres textes, 1979- LaivaNuit (suom. Christina Haataja, 1994)

- Les Yeux ouverts, 1980

- L'Été 80, 1980

- Vera Baxter, 1980 (screenplay)

- L'Homme assis dans le couloir, 1980

- Césarée, 1980 (screenplay)

- Agatha et les lectures illimitées, 1981 (director, screenplay)- film 1981, prod. Institut National de l'Audiovisuel (INA), Productions Berthemont, starring Bulle Ogier, Yann Andréa

- L'Homme atlantique, 1981 (director, screenplay)- film 1981, starring Yann Andréa, Marguerite Duras

- Outside: Papiers d'un jour, 1981- Outside: Selected Writings (translated by Arthur Goldhammer, 1986)

- Marguerite Duras à Montréal, Montreal, 1981 (edited by Suzanne Lamy and André Roy)

- Agatha, 1981- Agatha; Savannah Bay. 2 Plays (translated by Howard Limoli, 1992)- Agatha (suom. Jussi Lehtonen, 2000)

- Dialogue de Rome, 1982 (director, screenplay)- film 1982, prod. Lunga Gittata Cooperativa, Rai Tre Radiotelevisione Italiana, starring Paolo Graziosi, Anna Nogara

- Savannah Bay, 1982- Agatha; Savannah Bay. 2 Plays (translated by Howard Limoli, 1992)

- La Maladie de la mort, 1983- The Malady of Death (translated by Barbara Bray, 1986)- Kuolemantauti: näytelmä (suomentanut Jukka Mannerkorpi, 1994)- short film 2003, dir. by Asa Mader, starring Anna Mouglalis, Stephan Crasneanski and Yann Goven

- Théâtre III, 1984

- Les Enfants, 1984 (screenplay, dir. with Jean Mascolo, Jean-Marc Turine)- film 1984, starring Axel Bogousslavsky, Daniel Gélin, Tatiana Moukhine, Martine Chevallier

- L'Amant, 1984- The Lover (translated by Barbara Bray, 1985)- Rakastaja (suom. Jukka Mannerkorpi, 1985)- film 1992, dir. by Jean-Jacques Annaud, starring Jane March, Tony Leung Ka Fai and Frédérique Meininger

- La Douleur, 1985- Douleur (translated by Barbara Bray, 1986) / The War: A Memoir (translated by Barbara Bray, 1986)- Tuska (suom. Jukka Mannerkorpi, 1987)

- La Musica deuxième: Théâtre, 1985 (produced)

- Anton Chekhov. La mouette, 1985 (translator)

- Les Enfants, 1985 (film, dir.)

- La Pute de la côte normande, 1986

- Les Yeux bleus, cheveux noirs, 1986- Blue Eyes, Black Hair (translated by Barbara Bray, 1989)

- La Vie matérielle, 1987- Practicalities: Marguerite Duras Speaks to Jérôme Beaujour (translated by Barbara Bray, 1993)

- Les Yeux verts, 1987- Green Eyes (translated by Carol Barko, 1990)

- Emily L., 1987- Emily L. (translated by Barbara Bray, 1989)

- Marguerite Duras, 1987 (interview)

- La Pluie d'été, 1990- Summer Rain (translated by Barbara Bray, 1992)

- L'Amant de la Chine du Nord, 1990- The North China Lover (translated by Leigh Hafrey, 1992)

- Yann Andréa Steiner, 1992- Yann Andrea Steiner: A Memoir (translated by Barbara Bray, 1993)

- Outside, tome 2: Le Monde extérieur , 1993

- Écrire, 1995- Writing (translated by Mark Polizzotti, 2011)- Kirjoitan (suom. Annika Idström, 2005)

- C'est tout, 1995- No More (translated by Richard Howard, 1998)- Ei muuta (suom. Kristina Haataja, 1995)

- Théâtre IV, 1999

- Cahiers de la guerre et autres textes, 2006- Wartime Writings: 1943-1949 (translated by Linda Coverdale, 2008)- Sodan vihkot ja muita kirjoituksia (suomentanut Matti Brotherus, 2008)

- Œuvres complètes, 2011 (2 vols., edited by Gilles Philippe et al.)