Oscar Wilde / The Happy Prince

Oscar Wilde / The Selfish Giant

Oscar Wilde / The Birthday of the Infanta

Oscar Wilde / The Nightingale and the Rose

Pam Norfolk / The Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde / Sometimes

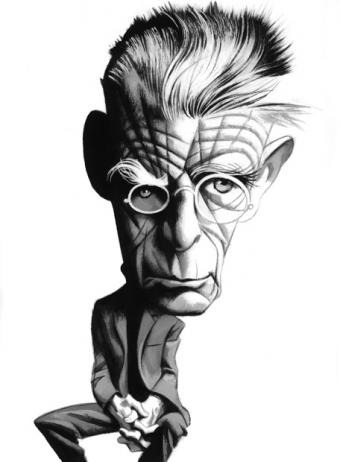

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde

(1854 - 1900)

Irish poet and dramatist whose reputation rests on his comic masterpieces Lady Windermere's Fan and The Importance of Being Earnest. Oscar Wilde's other best-known works include his only novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), which deals very similar theme as Robert Louis Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1886). Wilde's fairy tales are very popular – the motifs have been compared to those of Hans Christian Andersen.

"When they entered they found, hanging upon the wall, a splendid portrait of their master as they had last seen him, in all the wonder of his exquisite youth and beauty. Lying on the floor was a dead man, in evening dress, with a knife in his heart. He was withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage. It was not till they had examined the rings that they recognized who it was." (in The Picture of Dorian Gray)

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde was born in Dublin to unconventional parents. His mother, Lady Jane Francesca Wilde (1820-96), was a poet and journalist. Her pen name was Sperenza. According to a story she warded off creditors by reciting Aeschylus. Wilde's father was Sir William Wilde, an Irish antiquarian, gifted writer, and specialist in diseases of the eye and ear, who founded a hospital in Dublin a year before Oscar was born. His work gained for him the honorary appointment of Surgeon Oculist in Ordinary to the Queen. Lady Wilde, who was active in the women's rights movement, was reputed to ignore her husbands amorous adventures.

Wilde studied at Portora Royal School, in Enniskillen, County Fermanagh (1864-71), Trinity College, Dublin (1871-74), and Magdalen College, Oxford (1874-78), where he was taught by Walter Patewr and John Ruskin. Already at the age of 13, Wilde's tastes in clothes were dandy's. "The flannel shirts you sent in the hamper are both Willie's mine are one quite scarlet and the other lilac but it is too hot to wear them yet," he wrote in a letter to his mother. Willie, whom he mentioned, was his elder brother. Lady Wilde's third and last child was a daughter, named Isola Francesca, who died young. It has been said that Lady Wilde insisted on dressing Oscar in girl's clothers because she had longed for a girl.

In Oxford Wilde shocked the pious dons with his irreverent attitude towards religion and was jeered at his eccentric clothes. He collected blue china and peacock's feathers, and later his velvet knee-breeches drew much attention. Wilde was taller than most of his contemporaries, and athletically built, but the subject of sport bored him. In 1878 Wilde received his B.A. and on the same year he moved to London.

Soon his lifestyle and humorous wit made him the most talked-about advocate of Aestheticism, the late 19th century movement in England that argued for the idea of art for art's sake. To earn his living, Wilde worked as art reviewer (1881), lectured in the United States and Canada (1882), and in Britain (1883-1884). Since his childhood, Wilde had studied the art of conversation. His talk was articulate, imaginative, and poetic. From the mid-1880s he was regular contributor for Pall Mall Gazette and Dramatic View. Between 1887 and 1889 he edited Woman's World magazine

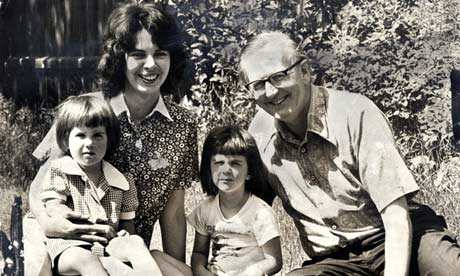

Wilde married in 1884 Constance Mary Lloyd, the daughter of John Horatio Lloyd, a wealthy barrister, and Ada Atkinson. Constance had enjoyed a throughout education, she played the piano well, was interested in arts, ambroidery, and could read Dante in Italian. For a short period she was a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. After she turned away from occultism she became involved in Christian socialism. Wilde himself had joined the Freemasons in the late 1870s.

On honeymoon in Paris Wilde and Constance visited the annual Paris salon, saw there Whistler's Harmony in Grey and Greenand went to opera to see Sarah Bernhardt in Macbeth. It is possible that before the marriage Wilde told Constance something of his sexual past. "... I am content to let the past be buried, it does not belong to me," she said in a letter, "I will hold you fast with chains of love." At Portora Royal School he had had some "sentimental friendships" with boys, and he had a encounter with a female prostitute in Paris while going steady with Constance. Their marriage ended in 1893, but the couple never divorced officially. Wilde's love letters to Constance have not survived.

The Happy Prince and Other Tales (1888), a collection of fairy-stories, Wilde wrote for his two sons, Cyril and Vyvyan. Possibly one of the strories, 'The Selfish Giant', was a joint effort between Wilde and Constance, who published her own collection, There Was Once in the same year. The Picture of Dorian Gray followed in 1890 and next year he brought out more fairy tales. Wilde had met an few years earlier Lord Alfred Douglas ("Bosie"), an athlete and a poet, who became both the love of the author's life and his downfall. "The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it," Wilde once said. Bosie's uncle, Lord Jim, caused a scandal when he filled in the 1891 census describing his wife as a "lunatic" and his stepson as a "shoeblack born in darkest Africa." During a stay in Paris, Wilde wrote Salomé in French. An anonymous English translation, dedicated to Alfred Douglas, was published in 1894. Richard Strauss's operatic version of the play was first performed in Dresden, five years after Wilde's death.

The Picture of Dorian Gray was published first by Lippincott's Monthly Magazine in 1890. Some of the homosexual content was censored by Lippincott editor J. M. Stoddart. Wilde revised the novel still further before it came out in expanded book form in 1891, added with six chapters. The book has some parallels with Wilde's own life. At Oxford he became a close friend of Frank Miles, a painter, and the homosexual aesthete Lord Ronald Gower, and it seems that they both are represented in Dorian Gray. In the story Dorian, a Victorian gentleman, sells his soul to keep his youth and beauty. The tempter is Lord Henry Wotton, who lives selfishly for amoral pleasure. "If only the picture could change and I could be always what I am now. For that, I would give anything. Yes, there's nothing in the whole world I wouldn't give. I'd give my soul for that." (from the film adaptation of 1945). Dorian starts his wicked acts, ruins lives, causes a young woman's suicide and murders Basil Hallward, his portrait painter, his conscience. However, although Dorian retains his youth, his painting ages and catalogues every evil deed, showing his monstrous image, a sign of his moral leprosy. The book highlights the tension between the polished surface of high life and the life of secret vice. In the end sin is punished. When Dorian destroys the painting, his face turns into a human replica of the portrait and he dies. "Ugliness is the only reality,'" summarizes Wilde.

Wilde made his reputation in theatre world between the years 1892 and 1895 with a series of highly popular plays. Lady Windermere's Fan (1892) dealt with a blackmailing divorcée driven to self-sacrifice by maternal love. In A Woman of No Importance (1893) an illegitimate son is torn between his father and mother. An Ideal Husband (1895) was about blackmail, political corruption and public and private honour. In The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), a comedy of manners, John Worthing (who prefers to call himself Jack) and Algernon Moncrieff (Algy) are two fashionable young gentlemen. "Relly, if the lower orders don't set us a good example, what on earth is the use of them?" John tells that he has a brother called Ernest, but in town John himself is known as Ernest and Algernon also pretends to be the profligate brother Ernest. Gwendolen Fairfax and Cecily Cardew are two ladies whom the two snobbish characters court. Gwendolen declares that she never travels without her diary because "one should always have something sensational to read in the train".

Before the theatrical success Wilde produced several essays, many of these anonymously. "Anybody can write a three-volume novel. It merely requires a complete ignorance of both life and literature," he once stated. His two major literary-theoretical works were the dialogues 'The Decay of Lying' (1889) and 'The Critic as Artist' (1890). In the latter Wilde lets his character state, that criticism is the superior part of creation, and that the critic must not be fair, rational, and sincere, but possessed of "a temperament exquisitely susceptible to beauty". The Soul of a Man Under Socialism (1891), a more traditional essay, takes an optimistic view of the road to socialist future. Wilde rejects the Christian ideal of self-sacrifice in favor of joy. "The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it."

Although married and the father of two children, Wilde's personal life was open to rumours. Constance had tolerated his infidelties and long absences from home, but his affair with Alfred Douglas (or 'Bosie') had a catastrophic effect on the marriage. In the midst of the crisis Constance found comfort from reading Dante's Inferno. During a separation from her husband in 1893 she took a portable Kodak camera with her to Italy, where she potographed buildings and some of the art pieces in Florence.

Wilde's years of triumph ended, when his intimate association with Alfred Douglas led to his trial on charges of homosexuality (then illegal in Britain). He was sentenced two years hard labour for the crime of sodomy. Constance went with her childred to Switzerland and then to Germany to escape the public eye. In 1895 she changed her and son's names to Constance, Cyril and Vyvyan Holland, taking the same family name her brother Otho used.

During his first trial Wilde defended himself, that "the 'Love that dare not speak its name' in this century is such a great affection of an eleder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare... There is nothing unnatural about it." Mr. Justice Wills, stated when pronouncing the sentence, that "people who can do these things must be dead to all senses of shame, and one cannot hope to produce any effect upon them." While he served his sentence, Bosie stood by Wilde, planned to dedicate a volume of poems to him, but the author felt himself betrayed and turned against him. Later they met in Naples, where they shared a villa. Constance visited Wilde in prison, too. Afterwards she wrote: "It was indeed awful more so than I had any conception it could be. I could not see him, I could not touch him, and I scarcely spoke."

Wilde was first in Wandsworth prison, London, and then Reading Gaol. When he was at last allowed pen and paper after more than 19 months of deprivation, Wilde had became inclined to take opposite views on the potential of humankind toward perfection. During this time he wrote De Profundis (1905), a dramatic monologue and autobiography, which was addressed to Alfred Douglas. "Everything about my tragedy has been hideous, mean, repellent, lacking in style. Our very dress makes us grotesques. We are the zanies of sorrow. We are the clowns whose hearts are broken." (in De Profundis)

After his release in 1897 Wilde lived under the name Sebastian Melmoth in Berneval, near Dieppe, then in Paris. He wrote The Ballad of Reading Gaol, revealing his concern for inhumane prison conditions. O n his death bed Wilde became a Roman Catholic. Wilde's friend Robbie Ross, who became his literary executor, brought a priest to his bedside. Wilde died of cerebral meningitis on November 30, 1900, penniless, in a cheap Paris hotel at the age of 46. He was first buried in the cemetery in Bagneux, and in 1909 his remains were removed to the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris.

"Do you want to know the great drama of my life," asked Wilde of André Gide. "It's that I have put my genius into my life; all I've put into my works is my talent." Constance died in 1898 in Genoa, after a spinal surgery. Her brother Otho blamed the surgeon, Signor Bossi, for his sister's death. Bossi was shot dead in 1919. Cyril was killed by a German sniper in 1915. Vyvyan, who also served in the army during WW I, gained fame as a translator and author. His son Merlin became an acknowledged Wilde scholar.

![]()

For further reading: Oscar Wilde: Art and Morality by Stuart Mason (1907); The Life and Confessions of Oscar Wilde by Frank Harris (1914); Oscar Wilde and Myself by Lord Alfred Douglas (1932); Oscar Wilde: The Critical Heritage, ed. Karl Beckson (1970);The Trials of Oscar Wilde by H. Montgomery Hyde (1975); Oscar Wilde: A Biography by H. Montgomery Hyde (1975); Oscar Wilde: Art and Egotism by Rodney Shewan (1977); Oscar Wilde by Richard Ellman (1987); Oscar Wilde: The Works of a Conformist Rebelby Norbert Kohl (1989); Rediscovering Oscar Wilde, ed. C. George Sandulescu (1993); Oscar and Bossie by Trevor Fisher (2002); A Portrait of Oscar Wilde by Merlin Holland (2008); Constance: The Tragic and Scandalous Life of Mrs Oscar Wilde by Franny Moyle (2011) - See also: André Gide, John Keats - Films: Oscar Wilde (1960), dir. Gregory Ratoff, starring Robert Morley, Phyllis Calvert, John Neville, Ralp Richardson. The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960), dir. Ken Hughes, starring Peter Finch, Yvonne Mitchell, Lionel Jeffries, Nigel Patrick, James Mason. Wilde (1998), dir. Brian Gilbert, starring Stephen Fry, Jude Law, Tom Wilkinson, Vanessa Redgrave, Jennifer Ehle.

Selected bibliography:

- Ravenna, 1878

- Vera, or the Nihilist, 1880 (drama)- Film: De Bannelingen, 1911, dir. Léon Boedels & Caroline van Dommelen, starring Caroline van Dommelen, Cato Mertens-de Jaeger and Louis van Dommelen

- Poems, 1881

- The Dutchess of Padua, 1883 (tragedy)

- Happy Prince and Other Tales, 1888 (contains The Happy Prince, The Nightingale and the Rose, The Selfish Giant, The Devoted Friend, The Remarkable Rocket)The Decay of Lying: An Observation, 1889

- Lord Arthur Savile's Crime and Other Stories, 1891

- - Films: Lord Saviles brott, 1922, starring Carl Alstrup; in Flesh and Fantasy, 1943, dir. Julien Duvivier; Voor donderdagavond twaalf uur Mylord (TV film), 1957, dir. Walter van der Kamp; Le Crime de Lord Arthur Saville, 1968, dir. André Michel; Prestuplenie lorda Artura (TV film), 1991, dir. Aleksandr Orlov; The Sum of Our Choices, 2010, dir. Oskar Flach

- Intentions, 1891 (includes The Decay of Lying)A House of Pomegranates, 1891

- 'The Soul of Man Under Socialism,' 1891 (in Pall Mall Gazette; as The Soul of Man, 1895, The Soul of Man Under Socialism, 1912)The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1891

- - Filmed several times: Dorian Grays Portræt, 1910, dir. Axel Strøm, starring Valdemar Psilander; 1913, dir. Phillips Smalley, starring Wallace Reid; Portret Doryana Greya, 1915, dir. Vsevolod Meyerhold, Mikhail Doronin, starring Varvara Yanova; 1915, dir. Matt Moore; 1916, dir. by Fred W. Durrant, starring Henry Victor; Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray, 1917, dir. Richard Oswald, starring Bernd Aldor; Az Élet királya, 1918,dir. Alfréd Deésy; 1945, dir. and written by Albert Lewin, starring Hurd Hatfield, George Sanders, Donna Reed; 1970, Dorian Gray, dir. Massimo Dallamano, starring Helmut Berger; 1977, Le Portrait de Dorian Gray, dir. Pierre Boutron, starring Patrice Alexsandre; Take Off (soft-porn version), 1978, dir. Armand Weston; Dorian, 2001, dir. Allan A. Goldstein, starring Ethan Erickson, Malcolm McDowell; 2004, dir. by David Rosenbaum, starring Josh Duhamel; 2006, dir. Duncan Roy, starring David Gallagher; Dorian Gray, 2009, dir. Oliver Parker, starring Ben Barnes, Colin Firth. See also: Faust theme and Goethe.

- Salomé, drame en un acte, 1892 (translated into English as Salome: A Tragedy in One Act, 1894)- Salome (suom. 1905)- Films: 1908, dir. J. Stuart Blackton; A Modern Salome, 1920, dir. Léonce Perret; 1923, dir. Charles Bryant; 1970, dir. Rafael Gassent; 1972, dir. Carmelo Bene; 1973, dir. Clive Barker, starring Anne Taylor, Graham Bickley, Clive Barker, Doug Bradley, Phil Rimmer; 1978, dir. Pedro Almodóvar, starring Isabel Mestres; 1986, dir. Claude d'Anna, starring Jo Champa; Salome's Last Dance, 1988, dir. Ken Russell, starring Glenda Jackson, Nickolas Grace, Stratford Johns, Imogen Millais-Scott

- Lady Windermere's Fan, 1893 (play, prod. 1892)- Films: 1916, dir. Fred Paul, starring Milton Rosmer, Netta Westcott and Nigel Playfair; 1925, dir. Ernst Lubitsch, starring Ronald Colman, May McAvoy, Bert Lytell, Irene Rich; Lady Windermeres Fächer, 1935, starring Lil Dagover, Walter Rilla, Hanna Waag; Shao nai nai de shan zi, 1939, dir. Pingqian Li; El Abanico de Lady Windermere, 1944, dir. Juan José Ortega; Historia de una mala mujer, 1948, dir. Luis Saslavsky, starring Dolores del Rio; The Fan, 1949, dir. Otto Preminger, starring Jeanne Crain, Madeleine Carroll, George Sanders, Richard Greene; A Good Woman, 2004, dir. Mike Barker, starring Helen Hunt, Scarlett Johansson

- Teleny, or The Reverse of the Medal, 1893 (anonymous, commonly attributed to Oscar Wilde)- Teleny (suomentanut Erkki Vainikkala, 1972)

- A Woman of No Importance, 1894 (comedy, prod.1893)- Films: 1912, prod. Powers Picture Plays; 1921, dir. Denison Clift; Eine Frau ohne Bedeutung, 1936, dir. Hans Steinhoff; Una Mujer sin importancia, 1945, dir. Luis Bayón Herrera; 2012, prod. Horizon Entertainment, Myriad Pictures, dir. Bruce Beresford, screenplay Howard Himelstein

- Poems in Prose, 1893-94, coll. 1905

- The Sphinx, 1894

- The Canterville Ghost, 1887- Films: 1944, dir. Jules Dassin, starring Charles Laughton; Kentervilskoe prividenie, 1962, dir. Valentina Brumberg & Zinaida Brumberg; Das Gespenst von Canterville, 1964, dir. Helmut Käutner, starring Barry McDaniel; O Caçador de Fantasma, 1975, dir. Flávio Migliaccio; TV film 1986, dir. Paul Bogart, starring John Gielgud; Neskolko stranits iz zhizni prizraka (animation), 1988, dir. M. Novogrudskaya; 1990, dir. Al Guest and Jean Mathieson; TV film 1995, dir. Syd Macartney, starring Patrick Stewart; Das Gespenst von Canterville, 2005, dir. Isabel Kleefeld, adaptation by Bettina Platz

- The Ballad of Reading Gaol, 1898The Importance of Being Earnest, 1899 (comedy, prod. 1895)

- - Films: Al compás de tu mentira, 1950, dir. Héctor Canziani; 1952, dir. Anthony Asquith, starring Michael Redgrave, Richard Wattis,Michael Denison, Walter Hudd; TV film 1985, dir. Michael Attenborough, Michael Lindsay- Hogg; TV film 1986, dir. Stuart Burge; 1992, dir. by Kurt Baker; 2002, dir. Oliver Parker, starring Rupert Everett, Colin Firth, Frances O'Connor, Reese Witherspoon, Judi Dench; TV film 2011, dir. Brian Bedford, David Stern, starring Dana Ivey, Brian Bedford and Paxton Whitehead

- An Ideal Husband, 1899 (drama, prod. 1895)- Filmed several times: Ein Idealer Gatte, 1935, dir. Herbert Selpin, starring Brigitte Helm, Sybille Schmitz and Karl Ludwig Diehl; Un Marido Ideal, 1947, dir. Luis Bayón Herrera; 1947, dir. by Alexander Korda, starring Paulette Goddard, Michael Wilding; Idealnyy muzh, 1980, dir. Viktor Georgiyev; 1998, dir. by William P. Cartlidge; 1999, dir. Oliver Parker, starring Rupert Everett, Cate Blanchett, Jeremy Northam, Julianne Moore; Ideální manzel (TV film), 2002, dir. Zdenek Zelenka

- De Profundis, 1905 (ed. Robert Ross, rev. ed. 1909, in full in The Letters, ed. Rupert Hart-Davis, 1962)- De profundis (suom. Helmi Setälä, 1907; Juhani Lindholm, 1997)

- A Florentine Tragedy, 1908 (tragedy, written 1894?)- Films: Een Florentijns treurspel (TV film), 1965, starring Sigrid Koetse, Ramses Shaffy and Ko van Dijk; En florentinsk tragedi (TV film),1965, dir. Lars Löfgren, starring Gunnel Broström, Allan Edwall and Georg Årlin

- Works, 1908-10 (4 vols., ed. Robert Ross)

- Resurgam, 1917 (ed. Clement Shorter)

- After Reading, 1921 (introduction, anonymously, by Stuart Mason)

- After Bwerneval, 1922 (introduction by More Adey)

- Some Letters from Oscar Wilde to Alfred Douglas, 1924 (ed. A.C. Dennison and Harrison Post)

- Oscar Wilde's Leters to Sarah Bernhardt, 1924 (ed. Sylvestre Dorian)

- Sixteen Letters from Oscar Wilde, 1930

- Letters to the Sphinx from Oscar Wilde, 1930

- The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, 1931

- The Portable Oscar Wilde, 1946 (ed. Richard Aldington)

- Complete Works, 1948 (ed. Wyvyan Holland)

- Essays, 1950 (ed. Hesketh Pearson)

- Selected Essays and Poems, 1954 (as De Profundis and Other Writings, 1973)

- The Letters of Oscar Wilde, 1962 (ed. Rupert Hart-Davis)

- Literary Criticism, 1968 (ed. Stanley Weintraub)

- The Artist as Critic: Critical Writings, 1969 (ed. Richard Ellmann)

- More Letters of Oscar Wilde, 1985 (ed. Rupert Hart-Davis)

- The Oxford Authors Oscar Wilde, 1989

- Oxford Notebooks: A Portrait of Maid in the Making, 1989 (ed. Philip E. Smith II and Michael S. Helfand)

- The Soul of Man, and Prison Writings, 1990 (ed. Isobel Murray)

- Aristotle at Afternoon Tea: The Uncollected Oscar Wilde, 1991 (ed. John Wyse Jackson)Works, 1993 (3 vols.. ed. Merlin Holland)

- Complete Letters of Oscar Wilde, 2000 (ed. Merlin Holland & Rupert Hart-Davis)

- Oscar Wilde: A Life in Letters, 2006 (ed. Merlin Holland)

- The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition, 2011 (ed. Nicholas Frankel)

http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/owilde.htm

This is my first memory: I'm taking a shower with one of my young aunts and I'm reaching for her pubis. She giggles and swirls around me. I'm standing on my own, but I don't talk yet. The bathroom where we're showering is the only place in our house I vaguely remember. The white-washed walls are damp, streaked with lichen growing around the edges of the cement floor. The house is in the town of Ciénaga, which means swamp. I know we lived in that house for the first two years of my life because of surviving telegrams sent to our house on Nuevo Callejón for my first two birthdays.

This is my first memory: I'm taking a shower with one of my young aunts and I'm reaching for her pubis. She giggles and swirls around me. I'm standing on my own, but I don't talk yet. The bathroom where we're showering is the only place in our house I vaguely remember. The white-washed walls are damp, streaked with lichen growing around the edges of the cement floor. The house is in the town of Ciénaga, which means swamp. I know we lived in that house for the first two years of my life because of surviving telegrams sent to our house on Nuevo Callejón for my first two birthdays.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

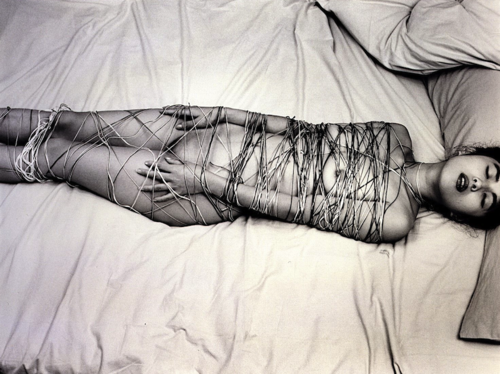

Photographer Nobuyoshi Araki was born in Tokyo, Japan, in 1940. In 1964, Araki was awarded by Taiyo magazine for his photographic work “Satchin”, a series which served as the basis for his debut solo exhibition, “Satchin and his brother Mabo”, in 1965. From 1970, Araki began the self publication and distribution of a series of Xerox books and the following year published the landmark, “Sentimental Journey”, featuring intimate images of his wife Yoko from the couple’s honeymoon. From the latter part of the 1970’s onwards, Araki began the publication of then and still controversial nude photographs as well as his prolific writings. 1991’s “Sentimental journey - winter’s journey” (Shinchosha), yet another seminal book within the history of Japanese photography, documented a decisive turning point in Araki’s life and career, the illness and death of Yoko by cancer in 1990. From 1992 on, a series of domestic and international exhibitions served to familiarize a wider audience with Araki’s practice. A selection of these exhibitions includes the Vienna Secession, Vienna and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (both 1999), the Barbican Art Gallery, London (2005) and the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima (2009). Over the course of a career spanning 45 years, Araki has published over 350 books. In 2008, Araki was awarded the Austrian Decoration of Honor for Science and Arts.

Photographer Nobuyoshi Araki was born in Tokyo, Japan, in 1940. In 1964, Araki was awarded by Taiyo magazine for his photographic work “Satchin”, a series which served as the basis for his debut solo exhibition, “Satchin and his brother Mabo”, in 1965. From 1970, Araki began the self publication and distribution of a series of Xerox books and the following year published the landmark, “Sentimental Journey”, featuring intimate images of his wife Yoko from the couple’s honeymoon. From the latter part of the 1970’s onwards, Araki began the publication of then and still controversial nude photographs as well as his prolific writings. 1991’s “Sentimental journey - winter’s journey” (Shinchosha), yet another seminal book within the history of Japanese photography, documented a decisive turning point in Araki’s life and career, the illness and death of Yoko by cancer in 1990. From 1992 on, a series of domestic and international exhibitions served to familiarize a wider audience with Araki’s practice. A selection of these exhibitions includes the Vienna Secession, Vienna and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (both 1999), the Barbican Art Gallery, London (2005) and the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art, Hiroshima (2009). Over the course of a career spanning 45 years, Araki has published over 350 books. In 2008, Araki was awarded the Austrian Decoration of Honor for Science and Arts.