(1923 - 1997)

During the course of a prolific career, Denise Levertov created a highly regarded body of poetry that reflects her beliefs as an artist and a humanist. Her work embraces a wide variety of genres and themes, including nature lyrics, love poems, protest poetry, and poetry inspired by her faith in God. "Dignity, reverence,and strength are words that come to mind as one gropes to characterize . . . one of America's most respected poets," wrote Amy Gerstler in the Los Angeles Times Book Review. Gerstler added that a "reader poking her nose into any Levertov book at random finds herself in the presence of a clear uncluttered voice—a voice committed to acute observation and engagement with the earthly, in all its attendant beauty, mystery and pain."

World Literature Today contributor Doris Earnshaw once described Levertov as being "fitted by birth and political destiny to voice the terrors and pleasures of the twentieth century. . . . She [had] published poetry since the 1940s that [spoke] of the great contemporary themes: Eros, solitude, community, war." Although born and raised in England, Levertov came to the United States when she was twenty-five years old, and all but her first few poetry collections have been described as thoroughly American. Early on, critics and colleagues alike detected an American idiom and style in her work, noting the influences of writers like William Carlos Williams, H. D. (Hilda Doolittle), Kenneth Rexroth, Wallace Stevens, and the projectivist Black Mountain poets. With the onset of the turbulent 1960s, Levertov delved into socio-political poetry and continued writing in this sphere; in Modern American Women Poets Jean Gould called her "a poet of definite political and social consciousness." However, Levertov refused to be labeled, and Rexroth once described her in With Eye and Earas "in fact classically independent."

Because Levertov never received a formal education, her earliest literary influences can be traced to her home life in Ilford, England, a suburb of London. Levertov and her older sister, Olga, were educated by their Welsh mother, Beatrice Adelaide Spooner-Jones, until the age of thirteen. The girls further received sporadic religious training from their father, Paul Philip Levertoff, a Russian Jew who converted to Christianity and subsequently moved to England and became an Anglican minister. In the Dictionary of Literary Biography, Carolyn Matalene explained that "the education [Levertov] did receive seems, like Robert Browning's, made to order. Her mother read aloud to the family the great works of nineteenth-century fiction, and she read poetry, especially the lyrics of Tennyson. . . . Her father, a prolific writer in Hebrew, Russian, German, and English, used to buy secondhand books by the lot to obtain particular volumes. Levertov grew up surrounded by books and people talking about them in many languages." It has been said that many of Levertov's readers favor her lack of formal education because they see it as an impetus to verse that is consistently clear, precise, and accessible. According to Earnshaw, "Levertov seems never to have had to shake loose from an academic style of extreme ellipses and literary allusion, the self-conscious obscurity that the Provencal poets called 'closed.'"

Levertov had confidence in her poetic abilities from the beginning, and several well-respected literary figures believed in her talents as well. Gould recorded Levertov's "temerity" at the age of twelve when she sent several of her poems directly to T. S. Eliot: "She received a two-page typewritten letter from him, offering her 'excellent advice.' . . . His letter gave her renewed impetus for making poems and sending them out." Other early supporters included critic Herbert Read, editor Charles Wrey Gardiner, and author Kenneth Rexroth. When Levertov had her first poem published in Poetry Quarterly in 1940, Rexroth professed: "In no time at all Herbert Read, Tambimutti, Charles Wrey Gardiner, and incidentally myself, were all in excited correspondence about her. She was the baby of the new Romanticism. Her poetry had about it a wistful Schwarmerei unlike anything in English except perhaps Matthew Arnold's 'Dover Beach.' It could be compared to the earliest poems of Rilke or some of the more melancholy songs of Brahms."

During World War II, Levertov pursued nurse's training and spent three years as a civilian nurse at several hospitals in the London area, during which time she continued to write poetry. Her first book of poems, The Double Image, was published just after the war in 1946. Although a few poems in this collection focus on the war, there is no direct evidence of the immediate events of the time. Instead, as noted above by Rexroth, the work is very much in keeping with the British neo-romanticism of the 1940s, for it contains formal verse that some consider artificial and overly sentimental. Some critics detect the same propensity for sentimentality in Levertov's second collection, Here and Now. In the National Review, N. E. Condini commented in retrospect on both of these volumes: "In The Double Image, a recurrent sense of loss prompts [Levertov] to extemporize on death as not a threat but a rite to be accepted gladly and honored. This germ of personal mythology burgeons in Here and Now with a fable-like aura added to it. . . . [ Here and Now] is a hymn to 'idiot' joy, which the poet still considers the best protection against the aridity of war and war's memories. Her weakness lies in a childish romanticism, which will be replaced later by a more substantial concision. Here the language is a bit too ornate, too flowery." Criticism aside, Gould said The Double Image revealed one thing for certain: "the young poet possessed a strong social consciousness and . . . showed indications of the militant pacifist she was to become."

Levertov came to the United States in 1948, after marrying American writer Mitchell Goodman, and began developing the style that was to make her an internationally respected American poet. Some critics maintain that her first American poetry collection, Here and Now, contains vestiges of the sentimentalism that characterized her first book, but for some, Here and Now displays Levertov's newly found American voice. Rexroth, for one, insisted in his 1961 collection of essays titled Assays that "theSchwarmerei and lassitude are gone. Their place has been taken by a kind of animal grace of the word, a pulse like the footfalls of a cat or the wingbeats of a gull. It is the intense aliveness of an alert domestic love—the wedding of form and content. . . . What more do you want of poetry? You can't ask much more." Gould claimed that by the time With Eyes at the Back of Our Heads was published in 1959, Levertov was "regarded as a bona fide American poet."

Levertov's American poetic voice was, in one sense, indebted to the simple, concrete language and imagery, and also the immediacy, characteristic of Williams Carlos Williams's art. Accordingly, Ralph J. Mills Jr. remarked in his essay in Poets in Progress that Levertov's verse "is frequently a tour through the familiar and the mundane until their unfamiliarity and otherworldliness suddenly strike us. . . . The quotidian reality we ignore or try to escape, . . . Levertov revels in, carves and hammers into lyric poems of precise beauty." In turn, Midwest Quarterly reviewer Julian Gitzen explained that Levertov's "attention to physical details [permitted her] to develop a considerable range of poetic subject, for, like Williams, she [was] often inspired by the humble, the commonplace, or the small, and she [composed] remarkably perceptive poems about a single flower, a man walking two dogs in the rain, and even sunlight glittering on rubbish in a street."

In another sense, Levertov's verse exhibited the influence of the Black Mountain poets, such as Robert Duncan, Charles Olson, and Robert Creeley, whom Levertov met through her husband. Cid Corman was among the first to publish Levertov's poetry in the United States in Origin in the 1950s. Unlike her early formalized verse, Levertov now gave homage to the projectivist verse of the Black Mountain era, whereby the poet "projects" through content rather than through strict meter or form. Although Levertov was assuredly influenced by several renowned American writers of the time, Matalene believed Levertov's "development as a poet [had] certainly proceeded more according to her own themes, her own sense of place, and her own sensitivities to the music of poetry than to poetic manifestos." Indeed, Matalene explained that when Levertov became a New Directions author in 1959, this came to be because editorJames Laughlin had detected in Levertov's work her own unique voice.

With the onset of the United States' involvement in Vietnam during the 1960s, Levertov's social consciousness began to more completely inform both her poetry and her private life. With Muriel Rukeyser and several other poets, Levertov founded the Writers and Artists Protest against the War in Vietnam. She took part in several anti-war demonstrations in Berkeley, California, and elsewhere, and was briefly jailed on numerous occasions for civil disobedience. In the ensuing decades she spoke out against nuclear weaponry, American aid to El Salvador, and the Persian Gulf War. The Sorrow Dance, Relearning the Alphabet, To Stay Alive, and, to an extent, Candles in Babylon, as well as other poetry collections, address many socio-political themes, like the Vietnam War, the Detroit riots, and nuclear disarmament. Her goal was to motivate others into an awareness of these various issues, particularly the Vietnam War and ecological concerns.

In contrast with the generally favorable criticism of her work, commentators tend to view the socio-political poems with a degree of distaste, often noting that they resemble prose more than poetry. In Contemporary Literature, Marjorie G. Perloff wrote: "It is distressing to report that . . . Levertov's new book, To Stay Alive, contains a quantity of bad confessional verse. Her anti-Vietnam War poems, written in casual diary form, sound rather like a versified New York Review of Books." Gould mentioned that some consider these poems "preachy," and Matalene noted that inRelearning the Alphabet Levertov's "plight is certainly understandable, but her poetry suffers here from weariness and from a tendency toward sentimentality. . . . To Stay Alive is a historical document and does record and preserve the persons, conversations, and events of those years. Perhaps, as the events recede in time, these poems will seem true and just, rather than inchoate, bombastic, and superficial. History, after all, does prefer those who take stands." In a Poetry magazine essay, Paul Breslin stated, "Even in the early poems, there is a moralizing streak . . . and when she engaged, as so many poets did, with the Vietnam War, the moralist turned into a bully: I agreed with her horrified opposition to the war, but not with her frequent suggestion that poets are morally superior because they are poets, and therefore charged with lecturing the less sensitive on their failures of moral imagination."

Contributor Penelope Moffet explained that in an interview with Levertov in Los Angeles Times Book Review just prior to the publication of Candles in Babylon,Levertov "probably would not go so far as to describe any of her own political work as 'doggerel,' but she does acknowledge that some pieces are only 'sort-of' poems." Moffet then quoted Levertov: "If any reviewer wants to criticize [ Candles in Babylon ] when it comes out, they've got an obvious place to begin—'well, it's not poetry, this ranting and roaring and speech-making.' It [the 1980 anti-draft speech included in Candles in Babylon] was a speech." Nevertheless, other critics were not so quick to find fault with these "sort-of" poems. In the opinion of Hayden Carruth, writing in Hudson Review,To Stay Alive "contains, what so annoys the critics, highly lyric passages next to passages of prose—letters and documents. But is it, after Paterson, necessary to defend this? The fact is, I think Levertov [had] used her prose bits better than Williams did, more prudently and economically. . . . I also think that To Stay Alive is one of the best products of the recent period of politically oriented vision among American poets." James F. Mersmann's lengthy analysis of several years of Levertov's poetry in Out of the Vietnam Vortex: A Study of Poets and Poetry against the Warcontains remarkable praise for the social protest poems. For contrast, Mersmann first analyzed Levertov's early poetry: "Balanced and whole are words that have perhaps best characterized the work and the person of Denise Levertov—at least until the late sixties. . . . There are no excesses of ecstasy or despair, celebration or denigration, naivete or cynicism; there is instead an acute ability to find simple beauties in the heart of squalor and something to relish even in negative experiences. . . . Through poetry she [reached] to the heart of things, [found] out what their centers are. If the reader can follow, he is welcomed along, but although the poetry is mindful of communication and expression, its primary concern is discovery." However, claimed Mersmann, the chaos of the war disrupted the balance, the wholeness, and the fundamental concern for discovery apparent in her work—"the shadow of the Vietnam War comes to alter all this: vision is clouded, form is broken, balance is impossible, and the psyche is unable to throw off its illness and sorrow. . . . A few notes of The Sorrow Dance sound something like hysteria, and later poems move beyond desperation, through mild catatonia toward intransigent rebellion. . . . In some sense the early poems are undoubtedly more perfect and enduring works of art, more timeless and less datable, but they are, for all their fineness, only teacups, and of sorely limited capacities. The war-shadowed poems are less clean and symmetrical but are moral and philosophical schooners of some size. . . . The war, by offering much that was distasteful and unsightly, prompted a poetry that asks the poet to add the light and weight of her moral and spiritual powers to the fine sensibility of her palate and eye."

Diane Wakoski, reviewing Levertov's volume of poems Breathing the Water, inWomen's Review of Books, stressed the religious elements in Levertov's work. "Levertov's poetry," Wakoski stated, "like most American mysticism, is grounded in Christianity, but like Whitman and other American mystics her discovery of God is the discovery of God in herself, and an attempt to understand how that self is a 'natural' part of the world, intermingling with everything pantheistically, ecologically, socially, historically and, for Levertov, always lyrically." Doris Earnshaw seemed to echo Wakoski in her review of Levertov's volume A Door in the Hive in World Literature Today. Earnshaw felt that Levertov's poems are "truly lyrics while speaking of political and religious affairs." The central piece of A Door in the Hive is "El Salvador: Requiem and Invocation," a libretto composed as a requiem for Archbishop Romero and four American woman who were killed by death squads in El Salvador in the early 1980s. Emily Grosholz stated in Hudson Review that while this is "not a poem, [it] is a useful kind of extended popular song whose proceeds served to aid important relief and lobbying efforts; such writing deserves a place side by side with Levertov's best poetry. And indeed, it is flanked by poems that rise to the occasion."

In a discussion of Levertov's volume Evening Train, World Literature Today reviewer Daisy Aldan believed the "collection reveals an important transition toward what some have called 'the last plateau': that is, the consciousness of entering into the years of aging, which she [experienced] and [expressed] with sensitivity and grace." Mark Jarman described the book in Hudson Review as "a long sequence about growing older, with a terrific payoff. This is the best writing she [has] done in years." Evening Train consists of individually titled sections, beginning with the pastoral "Lake Mountain Moon" and ending with the spiritually oriented "The Tide." In between, Levertov deals both with problems of personal conscience and social issues, such as AIDS, the Gulf War, pollution, and the ongoing threat of nuclear annihilation. Los Angeles Times Book Review contributor Amy Gerstler stated that all of the poems "blend together to form one long poem," and credited Levertov with possessing "a practically perfect instinct for picking the right distance to speak from: how far away to remain from both reader and subject, and how much of an overt role to give herself in the poem." Aldan concluded that the poems in Evening Train "manifest a new modesty, a refinement, sensibility, creative intelligence, compassion and spirituality."

In addition to being a poet, Levertov taught her craft at several colleges and universities nationwide; she translated a number of works, particularly those of the French poet Jean Joubert; she was poetry editor of the Nation from 1961-62 andMother Jones from 1976-78; and she authored several collections of essays and criticism, including The Poet in the World, Light up the Cave, and New & Selected Essays.

According to Carruth, The Poet in the World is "a miscellaneous volume, springing from many miscellaneous occasions, and its tone ranges from spritely to gracious to, occasionally, pedantic. It contains a number of pieces about the poet's work as a teacher; it contains her beautiful impromptu obituary for William Carlos Williams, as well as reviews and appreciations of other writers. But chiefly the book is about poetry, its mystery and its craft, and about the relationship between poetry and life. . . . It should be read by everyone who takes poetry seriously." Other reviewers also recommend the work to those interested in the craft of poetry since, as New Republiccommentator Josephine Jacobsen put it, "Levertov [spoke] for the reach and dignity of poetry. . . . [The book] makes . . . large claims for an art form so often hamstrung in practice by the trivial, the fake and the chic. It is impossible to read this book, to listen to its immediacy, without a quickening."

The essays in Light up the Cave, in turn, were considered "a diary of our neglected soul" by American Book Review critic Daniel Berrigan: "Norman Mailer did something like this in the sixties; but since those heady days and nights, he, like most such marchers and writers, has turned to other matters. . . . Levertov [is] still marching, still recording the march." Library Journal contributor Rochelle Ratner detected much maturation since the earlier Poet in the World, and Ingrid Rimland once remarked in the Los Angeles Times Book Review that "the strong impression remains that here speaks a poet intensely loyal to her craft, abiding by an artist's inner rules and deserving attention and respect. . . . This volume is a potpourri: assorted musings, subtle insights, tender memories of youth and strength, political passions, gentle but respectful accolades to other writers. The prose is utterly free of restraints, save those demanded by a fierce, independent spirit insisting at all times on honesty."

New & Selected Essays brings together essays dating from 1965 to 1992 and includes topics such as politics, religion, the influence of other poets on Levertov, the poetics of free verse, the limits beyond which the subject matter of poetry should not go, and the social obligations of the poet. Essays on poets who influenced Levertov cover William Carlos Williams, Robert Duncan, and Rainer Maria Rilke. Mary Kaiser, writing inWorld Literature Today, said of the collection: "Wide-ranging in subject matter and spanning three decades of thought, Levertov's essays show a remarkable coherence, sanity, and poetic integrity." Booklist writer Ray Olsen felt that some of the best essays included are the ones on technical aspects of poetry, singling out four essays on William Carlos Williams' variable foot as "some of the most illuminating, sensible, exciting Williams commentary ever written." Olsen concluded, "Next to poetry itself, this is ideal reading for lovers of poetry."

Levertov's 1995 work, Tesserae: Memories and Suppositions, contains twenty-seven autobiographical prose essays. The title, "tesserae," refers to the pieces that make up a mosaic, but as Levertov pointed out in her introduction to the work, "These tesserae have no pretensions to forming an entire mosaic." Instead of a full-scale memoir, the pieces reflect distinct memories about the author's parents, her youth, and her life as a poet. Reviewers remarked on the lyrical quality of Levertov's prose and on her spare, contained memories. A Publishers Weekly reviewer stated that Levertov's "ability to relate an incident is at once timeless and immediate, boundless and searingly personal."

Levertov died of lymphoma at the age of seventy-four. Almost until the moment of her death she continued to compose poetry, and some forty of them were published posthumously in This Great Unknowing: Last Poems. The work, while retaining an elegiac feel, also displays "the passion, lyrical prowess, and spiritual jubilation" that informed the end of Levertov's life, noted a reviewer in Sojourners. Noting that the book ranges from "the specifically personal to the searchingly mystical," a Publishers Weekly critic felt that it rises "to equal the splendor of Levertov's humane vision."

Discussing Levertov's social and political consciousness in his review of Light up the Cave, Berrigan stated: "Our options [in a tremulous world], as they say, are no longer large. . . . [We] may choose to do nothing; which is to say, to go discreetly or wildly mad, letting fear possess us and frivolity rule our days. Or we may, along with admirable spirits like Denise Levertov, be driven sane; by community, by conscience, by treading the human crucible." A contributor in Concise Dictionary of American Literary Biography commended Levertov for "the emphasis in her work on uniting cultures and races through an awareness of their common spiritual heritage and their common responsibility to a shared planet."

CAREER

Poet, essayist, editor, translator, and educator. Worked as a civilian nurse in numerous hospitals in London, 1943-45; worked in an antique store and a bookstore in London, 1946; in early career also taught English in Holland for three months; Young Men and Women's Christian Association (YM-YWCA) poetry center, New York, NY, teacher of poetry craft, 1964; Drew University, Madison, NJ, visiting lecturer, 1965; City College of the City University of New York, New York, NY, writer-in-residence, 1965-66; Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY, visiting lecturer, 1966-67; University of California, Berkeley, visiting professor, 1969; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, visiting professor and poet-in-residence, 1969-70; Kirkland College, Clinton, NY, visiting professor, 1970-71; University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, Elliston Lecturer, 1973; Tufts University, Medford, MA, professor, 1973-79; Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, Fannie Hurst Professor (poet-in-residence), 1981-83; Stanford University, Stanford, CA, professor of English (professor emeritus), beginning 1981. Co-initiator of Writers and Artists Protest against the War in Vietnam, 1965; active in the anti-nuclear movement.

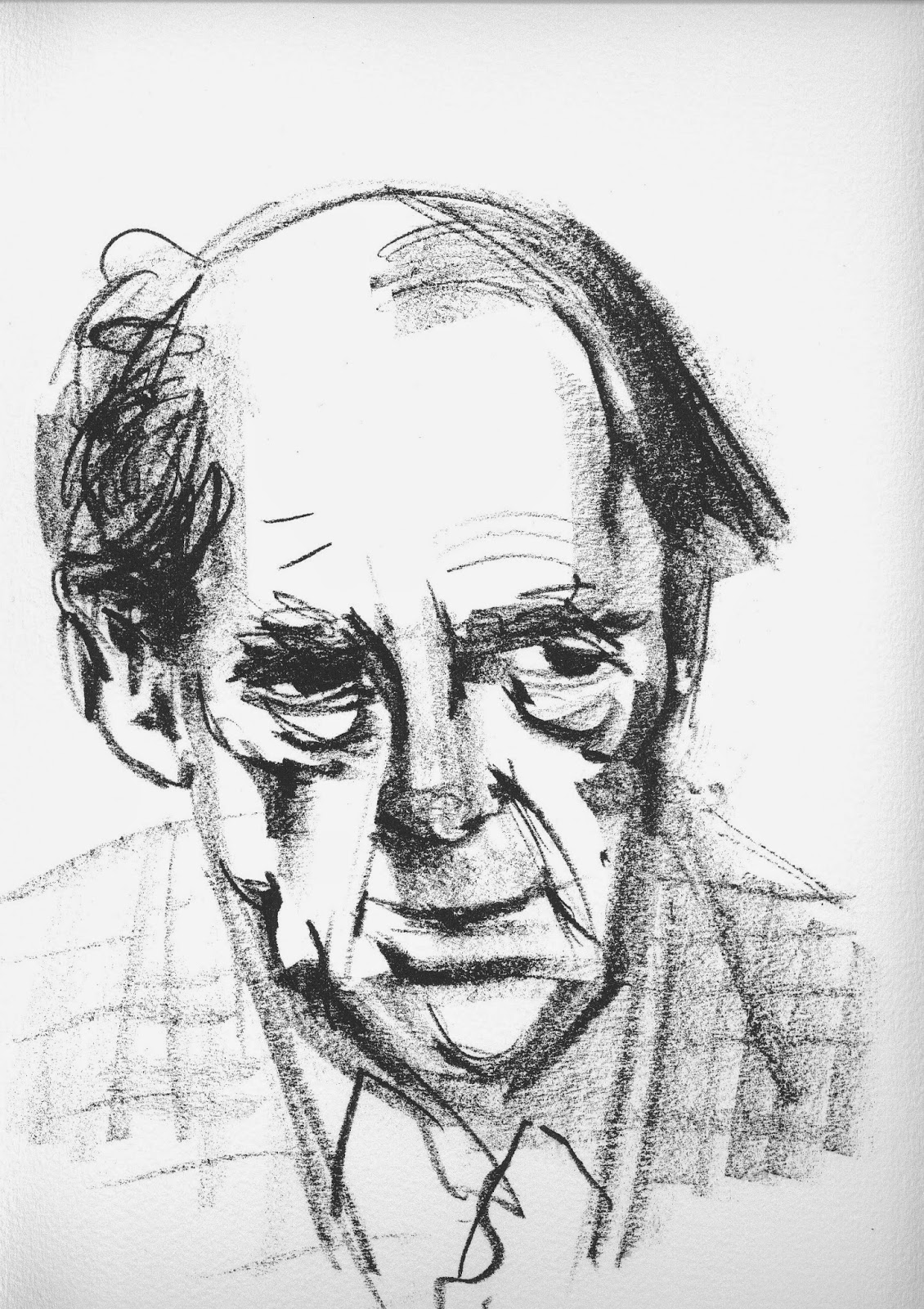

Robert Creeley on Denise Levertov

Hard to believe we met about fifty years ago in New York, when she and Mitch had first married and she had returned from Europe with him in the classic manner to start her own life over again. Certainly as a poet she had to. The distance between her first book,The Double Image, and the second, Here and Now, published by City Lights in its Pocket Poets series ten years later, is a veritable quantum leap. Kenneth Rexroth, editing The New British Poets for New Directions, thought her most able and, when he saw her, declared her Dante's Beatrice incarnate. W. C. Williams, writing of "Mrs. Cobweb" in Here and Now, said that one can't really tell if she's utterly virginal or if she has been on the town for years and years. Everyone was intrigued!

Was it Denise's long training as a dancer, when she was a child, that gave her such particularity of movement--her phrase and line shifting with the fact of her emotion, the rhythms locating each word? In a sense she was a wide-awake dreamer; a practical visionary with an indomitable will; a passionate, whimsical heart committed to an adamantly determined mind. It wasn't simply that Denise was right. It was that her steadfast commitments could accommodate no error.

I remember, when we were neighbors in France, riding our bicycles in Aix from the villages we lived in just to the north. There was a week-long celebration of Mozart. Denise's bike lost its brakes at the top of the three-mile hill into the city and down she came, full tilt, careening through early evening traffic, to come to rest finally at the far side near the railroad station. Was she terrified? I recall our going to the concert--so seemingly she soon recovered. Balance, quick purchase, passional measure rather than didactic, mind an antenna, not a quanitifier merely. Her voice was lovely. Her laughter, particularly her helpless, loud giggles, were what finally must define "humanness." Her whole body took over. We used to sit out at the edge of the orchard near her house in Puyricard, rehearsing endlessly what it was Williams was doing with the line. We were fascinated by how the pace was managed, how the insistent breaking into of the grammatically ordered line made a tension and a means more deft than any we had known. That bond of recognition, shared between us, never lessened.

Back in the States, then to Mexico, as I also shifted about to Black Mountain--then to New Mexico, Guatemala, and Canada--Mitch's and Denise's son Nick grew and grew, as our own children did. Thanks to Donald Allen's The New American Poetry (with Denise ostensibly the one woman of Black Mountain's company, despite the fact that she never went there, even to look), we began to have a public condition, as they say. The Vancouver Poetry Festival of 1963 and the Berkeley Poetry Conference of 1965 were the greatest collective demonstrations.

Necessarily the Vietnam War and its politics bitterly changed our world. Insofar as that determinant in Denise's life is a solid fact of the period's history, there's no need now to rehearse it. I was closest to the poems of The Jacob's Ladder and O Taste and See. Repeatedly she found voices for our common lives.

Years passed, of course. We saw one another all too rarely and yet her presence, her stalwart integrity, were always a given. Work to offset the world's real ills became an increasing occupation, forcing a more generalized community, on one hand, and also an increased singularity as her son moved into his own life and she and his father separated. She has written poignantly, healingly, of this time.

Now and then we would intersect on our show biz travels, once in Cincinnati, then a few days later in New York. Finally we were together at a Poetry Society of America awards dinner--we'd been judges--after she had moved to Seattle. Nick was with her; they were both solid and happy. There was always much I wanted to talk to her about--[Robert] Duncan, for example; my own confusions; the life I now lived with my family; the increased rigors of teaching. But we no longer seemed to find time or occasion to write. Last fall at Stanford, I got the news from friends that her cancer treatment seemed to have gone well. She had visited just a short time before and appeared much better.

Then bleakly, irrevocably, she was dead. No more chance to talk except in the way one finally always had--in what she wrote, what one had hoped to say, what one remembered.

-Originally published in Crossroads, 1997.

Levertov's gift for details is matched by the way she can make yearnings and ideas seem almost physical, as if she had them in the palm of her hand.

—Village Voice Literary Supplement

BIBLIOGRAPHY

POETRY

The Double Image, Cresset (Philadelphia, PA), 1946, reprinted Brooding Heron Press (Waldron Island, WA), 1991.

Here and Now, City Lights (San Francisco, CA), 1957.

5 Poems, White Rabbit Press (San Francisco, CA), 1958.

Overland to the Islands, J. Williams (Highlands, NC), 1958.

With Eyes at the Back of Our Heads, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1959.

The Jacob's Ladder, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1961.

O Taste and SEE: New Poems, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1964.

City Psalm, Oyez (Kensington, CA), 1964.

Psalm concerning the Castle, Perishable Press (Mount Horeb, WI), 1966.

The Sorrow Dance, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1967.

(With Kenneth Rexroth and William Carlos Williams) Penguin Modern Poets 9, Penguin (London, England), 1967.

A Tree Telling of Orpheus, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, CA), 1968.

A Marigold from North Vietnam, Albondocani Press-Ampersand (Everett, WA), 1968.

Three Poems, Perishable Press (Mount Horeb, WI), 1968.

The Cold Spring and Other Poems, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1969.

Embroideries, Black Sparrow Press (Santa Barbara, CA), 1969.

Relearning the Alphabet, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1970.

Summer Poems 1969, Oyez (Kensington, CA), 1970.

A New Year's Garland for My Students, MIT 1969-1970, Perishable Press (Mount Horeb, WI), 1970.

To Stay Alive, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1971.

Footprints, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1972.

The Freeing of the Dust, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1975.

Chekhov on the West Heath, Woolmer/Brotherston (Revere, PA), 1977.

Modulations for Solo Voice, Five Trees Press (San Francisco, CA), 1977.

Life in the Forest, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1978.

Collected Earlier Poems, 1940-1960, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1979.

Pig Dreams: Scenes from the Life of Sylvia, Countryman Press (Woodstock, VT), 1981.

Wanderer's Daysong, Copper Canyon Press (Port Townsend, WA), 1981.

Candles in Babylon, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1982.

Poems, 1960-1967, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1983.

Two Poems, William B. Ewert (Concord, NH), 1983.

Oblique Prayers: New Poems with Fourteen Translations from Jean Joubert, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1984.

El Salvador: Requiem and Invocation, William B. Ewert (Concord, NH), 1984.

The Menaced World, William B. Ewert (Concord, NH), 1984.

Selected Poems, Bloodaxe Books (Newcastle upon Tyne, England), 1986.

Breathing the Water, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1987.

Poems, 1968-1972, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1987.

(With Peter Brown) Seasons of Light, Rice University Press (Houston, TX), 1988.

A Door in the Hive, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1989.

Evening Train, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1992.

Sands of the Well, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1996.

Batterers, Janus Press (West Burke, VT), 1996.

The Life around Us: Selected Poems on Nature, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1997.

The Stream and the Sapphire: Selected Poems on Religious Themes, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1997.

This Great Unknowing: Last Poems, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1999.

Poems: 1972-1982, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 2001.

OTHER

(Translator and editor, with Edward C. Dimock, Jr.) In Praise of Krishna: Songs from the Bengali, Doubleday (New York, NY), 1967.

(Editor) Out of the War Shadow: An Anthology of Current Poetry, War Resisters League, 1967.

In the Night: A Story, Albondocani Press (New York, NY), 1968.

(Contributor of translations) Jules Supervielle, Selected Writings, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1968.

(Translator from French) Eugene Guillevic, Selected Poems, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1969.

The Poet in the World (essays), New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1973.

Light up the Cave (essays), New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1981.

Mass for the Day of St. Thomas Didymus, William B. Ewert (Concord, NH), 1981.

(Translator, with others from Bulgarian) William Meredith, editor, Poets of Bulgaria, Unicorn Press (Greensboro, NC), 1985.

(Translator from French) Jean Joubert, Black Iris, Copper Canyon Press (Port Townsend, WA), 1988.

(Translator, with others from French) Alain Bosquet, No Matter No Fact, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1988.

El paisaje interior (essays translated to Spanish by Patricia Gola), Universidad Autonoma de Tlaxcala (Tlaxcala, Mexico), 1990.

(Translator) Jean Joubert, White Owl and Blue Mouse, Zoland Books (Cambridge, MA), 1990.

New & Selected Essays, New Directions (New York, NY), 1992.

Tesserae: Memories and Suppositions (autobiographical essays), New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1995.

Conversations with Denise Levertov, edited by Jewel Spears Brooker, University Press of Mississippi (Jackson, MS), 1998.

The Letters of Denise Levertov and William Carlos Williams, edited by Christopher MacGowan, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1998.

(Editor and author of foreword) John E. Smelcer, Songs from an Outcast: Poems, American Indian Studies Center, University of California (Los Angeles, CA), 2000.

Also author of Lake, Mountain, Moon, 1990. Contributor to New American Poetry, Grove (New York, NY), 1960;Parable, Myth, and Language, Church Society for College Work (Cambridge, MA), 1967; The Bloodaxe Book of Contemporary Women Poets, Bloodaxe Books (Newcastle upon Tyne, England), 1984; and American Poetry Observed: Poets and Their Work, University of Illinois Press (Chicago, IL), 1984. Contributor of poetry and essays to numerous periodicals. Poetry editor, Nation, 1961-62, and Mother Jones, 1976-78. Levertov's main manuscript collection is housed at the Green Library, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Other collections are housed in the following locations: Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin; Washington University, St. Louis, MO; Indiana University, Bloomington; Fales Library, New York University, New York; Beinecke Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT; Brown University, Providence, RI; University of Connecticut, Storrs; Columbia University, New York, NY; and State University of New York at Stony Brook.

![]()

FURTHER READING

BOOKS

Breslin, James E. B., From Modern to Contemporary: American Poetry, 1945-1965, University of Chicago Press (Chicago, IL), 1984, pp. 143-155.

Brooker, Jewel Spears, Conversations with Denise Levertov, University Press of Mississippi (Jackson, MS), 1998.

Capps, Donald, The Poet's Gift: Toward the Renewal of Pastoral Care, Westminister/John Knox (Louisville, KY), 1993.

Concise Dictionary of American Literary Biography Supplement: Modern Writers, 1900-1998, Gale (Detroit, MI), 1998.

Contemporary Literary Criticism, Volume 66, Gale (Detroit, MI), 1991.

Contemporary Poets, sixth edition, St. James Press (Detroit, MI), 1996.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 5: American Poets since World War II, 1980, Volume 165: American Poets since World War II, Fourth Series.

Feminist Writers, Gale (Detroit, MI), 1996.

Gelpi, Albert, editor, Denise Levertov: Selected Criticism, University of Michigan Press (Ann Arbor, MI), 1993.

Gould, Jean, Modern American Women Poets, Dodd (New York, NY), 1985.

Hungerford, Edward, editor, Poets in Progress, second edition, Northwestern University Press (Evanston, IL), 1967.

Kinnahan, Linda A., Poetics of the Feminine: Authority and Literary Tradition in William Carlos Williams, Mina Loy, Denise Levertov, and Kathleen Fraser, Cambridge University Press (Cambridge, England), 1994.

Levertov, Denise, Tesserae: Memories and Suppositions, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1995.

Marten, Harry, Understanding Denise Levertov, University of South Carolina Press (Columbia, SC), 1988.

Mersmann, James, Out of the Vietnam Vortex: A Study of Poets and Poetry against the War, University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, KS), 1974.

Middleton, Peter, Revelation and Revolution in the Poetry of Denise Levertov, Binnacle Press (London, England), 1981.

Rexroth, Kenneth, Assays, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1961.

Rexroth, Kenneth, With Eye and Ear, Herder & Herder (Lanham, MD), 1970.

Rodgers, Audrey T., Denise Levertov: The Poetry of Engagement, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press (Rutherford, NJ), 1993.

Sakelliou-Schultz, Liana, Denise Levertov: An Annotated Primary and Secondary Bibliography, Garland Publishing (New York, NY), 1988.

Slaughter, William, The Imagination's Tongue: Denise Levertov's Poetic, Aquila, 1981.

Wagner, Linda W., Denise Levertov, Twayne (New Haven, CT), 1967.

Wagner, Linda W., editor, Denise Levertov: In Her Own Province, New Directions Press (New York, NY), 1979.

Wagner-Martin, Linda W., editor, Critical Essays on Denise Levertov, G. K. Hall (Boston, MA), 1990.

Wilson, Robert A., A Bibliography of Denise Levertov, Phoenix Book Shop (New York, NY), 1972.

PERIODICALS

America, November 13, 1993, p. 19; May 30, 1998, Judith Dunbar, "Denise Levertov: 'The Sense of Pilgrimage,'" p. 22.

American Book Review, January-February, 1983; October, 1993, p. 7.

Booklist, October 15, 1992, p. 394; April 15, 1995, p. 1468.

Christian Science Monitor, June 3, 1993, p. 16.

Contemporary Literature, winter, 1973.

Hudson Review, summer, 1990, pp. 328-329; summer, 1993, pp. 415-424.

Kirkus Reviews, March 1, 2001, review of Poems: 1972-1982, p. 302.

Library Journal, September 1, 1981; April 15, 1995, p. 80; May 1, 1996, p. 97.

Los Angeles Times Book Review, June 6, 1982; July 18, 1982; December 27, 1992, p. 5; April 30, 1995, p. 6.

Michigan Quarterly Review, fall, 1985.

Midwest Quarterly, spring, 1975.

Nation, August 14, 1976.

National Catholic Reporter, May 22, 1998, Patty McCarty, review of Sands of the Well, p. 36.

National Review, March 21, 1980.

New Republic, January 26, 1974.

New York Times Book Review, January 7, 1973; November 30, 1975.

Poetry, June, 2000, Paul Breslin, "Black Mountain Reunion," p. 159.

Publishers Weekly, March 13, 1995, p. 55; February 26, 1996, p. 101; October 19, 1998, review of The Letters of Denise Levertov and William Carlos Williams, p. 66; March 29, 1999, review of This Great Unknowing: Last Poems, p. 98.

Sojourners, November, 1999, review of This Great Unknowing: Last Poems, p. 56.

Village Voice, September 29, 1987.

Washington Post, July 11, 1999, review of This Great Unknowing: Last Poems.

Women's Review of Books, February, 1988, pp. 7-8.

World Literature Today, winter, 1981; spring, 1983; summer, 1985; autumn, 1990, p. 640-641; autumn, 1993, p. 832; winter, 1994, pp. 132-133.

OBITUARIES

Chicago Tribune, December 23, 1997, section 1, p. 10.

Los Angeles Times, December 23, 1997, p. A26.

New York Times, December 23, 1997, p. B8.

Time, January 12, 1998, p. 31.

Washington Post, December 23, 1997, p. B7; January 6, 1998, p. A12.

.jpg)